The Law and Bench of High Court under the Constitution of India

By O.V. Radhakrishnan, Senior Advocate, High Court of Kerala

26/05/2008

26/05/2008

The Law and Bench of High Court under the Constitution of India

(By O.V. Radhakrishnan, Sr.Advocate)

Under the Constitution of India, High Court is the supreme judicial institution and superior court of record of the State Judiciary. Art.214 of the Constitution of India directs that there shall be a High Court for each State. All the High Courts enjoy the same status although they do not constitute a single all India judicial cadre. A Judge is appointed to a particular High Court. But the President may transfer a Judge from one High Court to any other High Court in exercise of the power under Art.222(1) of the Constitution. A High Court is constituted on the appointment of Chief Justice no matter other Judges are appointed or not. The Chief Justice can perform his duties and also discharge his function as a Single Judge in the absence of other Judges. "The Judges of a High Court owe their responsibilities and discharge their functions in relation to that High Court only. They have no constitutional connection and no legal relationship with the body of Judges of any other High Court" (S. P. Gupta v. Union of India (1981 (Supple) SCC 87) per Pathak Judgment.). Therefore, there shall be only one High Court for each State and each High Court is independent and indivisible. Exception is made in Art.231 for establishment of a common High Court for two or more States or two or more States and a Union Territory. Its integrity as a court of record shall be preserved having realistic regard to the setting and scheme of the Constitution.

"High Court" is defined under Art.366(14) of the Constitution to mean any court which is deemed for the purposes of the Constitution to be a High Court for any State and includes -- (a) any court in the territory of India constituted or reconstituted under the Constitution as a High Court, and (b) any other court in the territory of India which may be declared by Parliament by law to be a High Court for all or any of the purposes of the Constitution. The above definition of High Court contemplates constitution or reconstitution as a High Court under the Constitution and declaring any other Court by the Parliament to be a High Court, but does not behold a Bench of a High Court. A Bench or a Division of High Court is outside the web of the Constitution. Therefore, providing a Bench to a High Court outside the seat of a High Court is legally impermissible and has no constitutional warrant. It is above the reach of competent legislation.

Art. 130 of the Constitution provides that the Supreme Court shall sit in Delhi or in such other place as the Chief Justice of India may, with the approval of the President, appoint. Art. 130 of the Constitution also does not empower to constitute or establish permanent Bench/ Benches in such other place or places but can only hear cases in such other place or places appointed by the Chief Justice of India with the approval of the President. Identical provision is conspicuously absent in respect of High Courts in the Constitution. Necessarily, to put on the language of Arts. 214 and 216 read with Art.366(14) rational meaning, it does not need research to show that power to set up a Bench of the High Court in other places outside the seat of the High Court is pro-tanto excluded. Any interstitial law making extending to direct conflict with express provisions of the Constitution or to ruling them out of existence is a misuse of power in bad faith.

The Parliament enacted the States Reorganization Act, 1956 to provide for the reorganization of the States of India and for matters connected therein. S. 51 of the Act relates to principal seat and other places of sitting of High Courts of new States which is quoted hereunder :-

S.51 (1) - The principal seat of the High Court of the new State shall be at such places as the President may by notified order appoint.

(2) The President may, after consultation with the new Governor of the new State and the Chief Justice of the High Court of that State, by notified order, provide for the establishment of a permanent Bench or Benches of that High Court at one or more places within the State other than the principal seat of the High Court and for any matters connected therewith.

(3) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-s. (1) or sub-s. (2), the Judges and Division of Courts of the High Court for the new State may also sit at such other place or places in that State as the Chief Justice may, with the approval of the Governor, appoint.

The above provision was designed to provide for the disposal of cases pending before certain High Courts and Benches, which under the provisions of the Act, were ceased to! function at particular places. According to S. 51 (2) of the Act 1956, it is within the province of the President to establish a permanent Bench of a High Court with a separate Registry after consultation with the Governor of the State and the Chief Justice of the respective High Court. In a Bench decision in Manickan Pillai Subbayya Pillai v. Assistant Registrar, High Court of Kerala, Trivandrum(1958 KLT 280.) the High Court of Kerala has held that" the Trivandrum Bench is not the High Court of Kerala is apparent from a mere perusal of S. 51(3) of the States Reorganization Act which states that the Judges and the Division Court of High Court for a new State may also sit at such other place or places in that State as the Chief Justice may, with the approval of the Governor, appoint. It is the Judges and Division Courts of the High Court of Kerala and not the High Court itself that sits at Trivandrum". It has also been held therein that "the principal seat of the High Court under S. 51(1) of the Act is the place where the High Court as a whole functions in all its capacity. The High Court as such is located there, and though the word 'sit' can be used in relation to a Court to denote its location (See Art. 130 of the Constitution and S. 6 of the Travancore-Cochin High Court Act and the marginal notes thereto) it is ordinarily used especially in connection with 'Judge' or 'Division Court' to denote sitting for the purpose of hearing cases". The Division Bench went on to hold that "the Trivandrum Bench can only hear and dispose of such cases as are directed to be posted before it by the Chief Justice. It cannot do anything else on behalf of the High Court, and in particular, it cannot receive cases".

In State of Maharashtra v. Narayan(AIR 1983 SC 46)) the Hon'ble Supreme Court has held that "it is difficult to comprehend how the Chief Justice can arrange for the sittings of the Judges andDivision Court at a particular place unless there is a seat at that place. It may be true in thejuristic sense that the seat of the High Court must mean "the principal seat" of such HighCourt, i.e., the place where the High Court is competent to transact every kind of businessfrom any part of the territories within its jurisdiction. It is impossible to conceive of a HighCourt without a seat being assigned to it. The place where it would sit to administer or, inother words, where its jurisdiction can be invoked is an essential and indispensable featureof the legal institution known as a Court". The Apex Court in the above decision did notapprove the view taken by Raman Nair, J. (as he then was), in Manickan Pillai's case speakingfor the Court that the Trivandrum Bench was not the High Court of Kerala and the Judgesand Division Courts sitting at Trivandrum could hear and dispose of only such cases as maybe assigned to them. The Apex Court preferred the view expressed by Chagla, C.J inManjidana's case(Seth Manjidana v. Commissioner of Income Tax, Bombay (Civil Appeal No. 995 of 1957 (Bom.) decided on July 22, 1958).) that the Judges and Division Courts at temporary bench establishedunder Sub-s.(3) of S. 51 of the Act function as Judges and Division Courts of the HighCourt at the principal seat and while so sitting at such a temporary Bench they may exercisethe jurisdiction and power of the High Court itself in relation to all the matters entrusted tothem. In the above judgment considered and decided by the Supreme Court there was nochallenge to the vires of S. 51 of the States Reorganization Act. Therefore, the decisionrendered in Stare of Maharashtra v. Narayanan turned on the provisions in the StatesReorganization Act and the question whether S. 51 of the States Reorganization Act to theextent it permits establishment of permanent Benches of High Courts at one or more placeswithin the State other than the principal seat of the High Court, collides with the constitutionalscheme remained unaddressed and undecided.

In Federation of Bar Associations in Karnataka v. Union of India ((2000) 6 SCC 715.) the Apex Court observed that it is inexpedient to be provided different Benches for the High Court located in different regions. To quote "Apart from the heavy burden such a Bench would inflict on the State exchequer, the functional efficiency of the High Court would be much impaired by keeping High Courts in different regions. When the Chief Justice of the High Court is a singular office, and when the Advocate General is a singular office, vivisection of the High Court into different Benches at different regions would undoubtedly affect the efficiency of the High Court".

Art.231 begins with a non-obstante clause and empowers the Parliament to make law to establish a common High Court for two or more States or for two or more States and Union Territory. The above Article operates as an exception to Art.214 and 216 by empowering the Parliament to establish a common High Court for two or more States and a Union Territory by force of the non-obstante clause provided at the beginning of that Article. That Article at any rate, does not empower the Parliament to make law to constitute or establish a Bench/Benches of a High Court, Arts.214 and 216 notwithstanding. It is obvious that the Constitution makers did not intend to provide Bench or Benches to High Court to preserveand to protect its integrity as a Court of record. The language used in Art.216 of the] Constitution is not similar to that used in Art. 130 as found by the Apex Court in Union on India and others v. S.P. Anand & Ors ((JT 1998 (5) SC 359).)

The States Reorganization Act is made in exercise of the constitutional power under Art.3 of the Constitution of India. Constitution, organisation, jurisdiction of High Courts fall outside the scope of Art. 3 of the Constitution. Constitutional powers can be exercised only in respect of matters specifically assigned in the Constitution. It may therefore, be seen that provisions in S. 51 of the States Reorganisation Act in so far as it empowers establishment of a permanent Bench or Benches to the High Court at one or more places within the State other than the principal seat of the High Court does not fall within the confines of Art.3. Hence it would be wrong, to give the impression that the constitutional provision in Art.214 got modified by S. 51 of the States Reorganization Act and the legal aspect in question covered by S. 51 of the States Reorganization Act. It cannot be legally argued that S. 51 of the States Reorganization Act is 'reasonably incidental' to or consequential upon, those things which the Constitution has authorised under Art. 3 of the Constitution.

The solution lies with the Parliament to exercise its constituent power under Art.368 of the Constitution. The only question is whether the High Courts do need different Benches in the interest of the general or litigating public?

To this question I return a negative response.

I conclude, borrowing the observations of Thomas J., in the Judgment in Federation of Bar Associations, Karnataka case ((2000) 6 SCC 715) "the question of establishment of a Bench of the High Court away from the principal seat of the High Court is not to be decided on emotional or sentimental or parochial considerations".

Concept of Welfare State and SEZ Act, 2005

By G. Krishna Kumar, Advocate, Ernakulam

19/05/2008

19/05/2008

*Concept of Welfare State and SEZ Act, 2005

(By G. Krishna Kumar, Advocate, Ernakulam)

Compulsory acquisition of land for public purpose is well accepted procedure from the ancient days itself. The object behind such compulsory acquisition is for public purpose, based on the principle of eminent domain "Welfare of the people is supreme law". So it is well within the powers of the State to acquire compulsorily, the properties of individuals, for public welfare to provide facilities and better living conditions to the people at large.

Our's is an agrarian economy and majority of the people are engaged in agriculture or agriculture related works. Economic reforms should be implemented keeping in mind the above aspects, unfortunately which is missing in the present day legislations. For example, our legislature has enacted 'Special Economic Zone Act, 2005 to provide for establishment, development and management of special Economic Zone for the promotion of exports. As per S. 3 of the Act, a private person can establish SEZ for manufacture of goods or rendering service. Acquisition of land to allot corporate companies is a new trend which will make weaker section more weaker and will amount to concentration of wealth in corporate groups.

Whether under the colour of trade promotion, can the Government accelerate concentration of wealth in certain persons or group of persons ? Can the Government Snatch away the property of downtrodden and transfer it to the corporate giants ? Is it not reverse discrimination against the helpless persons belonging to lower strata of the society?

Before answering these questions, let us examine the concept of socialist, welfare State enshrined in the Constitution.

Preamble, which is the golden Key of the Constitution guarantees that India should be a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic, republic and assure to all its citizens, Justice: Social, Economic and Political and also assure equality of status and opportunities. Preamble embodies hopes and aspirations of the people.

Part IV of the Constitution contains directive principles which will govern the State and its instruments in it's affairs. The concept of 'welfare state' should be understood in the light of dream concept of our Father of Nation to make India a 'Ramarajya'. Art. 14 of the Constitution guarantees equality before law and equal protection of law. It is settled law that equal treatment of unequal itself is denial of equality. So the State should endeavour to enact laws to protect weaker section of the society. Art. 39(c) forbids the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment. Art. 39(b) prescribes that the ownership and control of material resources of the community are so distributed as best to sub serve the common good. Art.39(a) prescribes that the State shall secure adequate means of livelihood to citizens. Art.41 mandates the Government to ensure right to work.

In Keshavanadha Bharathi case the Apex Court considering the constitutional validity ((1973) 4 SCC 225. ) of Land Reforms Act held that Art 39, together with other provisions of the Constitution contains one main objective, namely the building of a Welfare State and an egalitarian social order to fix certain social and economic goals for immediate attainment by bringing about a non-violent social revolution. It was further held that "Through such a social revolution, the Constitution seeks to fulfil the basic need of the common man and to change the structure of the society, without which political democracy has no meaning".

In Sanjeev Coke Mfg. Co.Ltd. v. Bharath Cooking Coal Ltd. (AIR 1983 SC 239) the Apex Court considering the constitutional validity of Coking Coal Mines Nationalisation Act, by upholding the Act held that Nationalisation of Coal mines, in whole or in part, is a law for implementation of Art.39(b). (See also Bank Nationalisation case AIR 1970 SC 564).

In Excel Wear v. Union of India (AIR 1979 SC 25.) The Honourable Supreme Court considered the impact of the term 'Socialist' in the preamble and held that the word 'socialist' enshrined in the preamble, read with Art. 39(d), would enable the court to uphold the constitutionality of nationalisation of private property.

The Honourable Supreme Court in Hakara D.S. v. Onion Of India (AIR 1983 SC 130.) considered the sprit of the word 'Socialist' in the preamble and held that the word 'socialist' read with Art 14 of the Constitution helps to strike down a statute which failed to achieve it at the fullest extent. In Atom Prakash v. State of Haryana held the term socialist r/w. Art 14 strike down discrimination which adopts a classification which is not in tune with the establishment of a welfare society. The Apex Court further held "Whatever article of the Constitution it is that the Court seeks to interpret, whatever statute it is whose constitutional validity is sought to be questioned, the Court must strive to give such an interpretation as will promote the march and progress towards a Socialistic Democratic State",

In a land mark decision Lingappa Pochaima Appelewar v. State of Maharashtra (AIR 1985 SC 389 (paras. 14,16,18, 20)) the Apex Court held that the expression 'social and economic justice' involves the concept of 'distributive justice' which connotes the removal of economic inequalities and rectifying the injustice resulting from dealings or transactions between unequal's in society. It comprehends more than lessening of inequalities by differential taxation, giving debt relief or regulation of contradictable relations; it also means the restoration of property to those who have been deprived of them by unconscionable bargains; It may also take the form of forced redistribution of wealth as a means of achieving a fair division of material resources among the members of society. In Dalmia Cement (Bharat) Ltd. case ((1996) 10SCC104.) the Supreme Court re-iterated that the ideal of economic justice is to make equality of status meaningful and life worth living at its best, removing inequality of opportunity and status -Social, Economic and Political.

In Ratlam Municipal Council case (AIR 1980 SC 1622.), the Apex Court held that the courts should have regard to the directive in Art. 38 to promote welfare of the people and social justice. In a land mark decision in G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology v. State of U.P. ((2000) 7 SCC 109.) it was held that Democratic socialism aims to end poverty, ignorance, disease and inequality of opportunity. The socialistic concept ought to be implemented in the true sprit of the Constitution.

The Apex Court in a yet another land mark decision in State of Tamil Nadu v. Ambalarana Pandara Samadhi Adheenakartha ((1997) 9 SCC 313.) held that Tenants/Tillers of soil have a fundamental right to economic empowerment u/Art. 39(b) and are entitled to Ryotvari Patta".

Art. 14. 1 5, 16, 21, 38, 39 and 46 read with preamble make the equality of the life of the poor, disadvantaged and disabled citizens of the society, meaningful. Art. 38 in particular is having the object of securing a welfare state and to be read together with Part III rights.

So discrimination is possible as per the Constitution. But it should always be in favour of weaker section. Only through equality in affirmative sense, equality enshrined under the Constitution will be meaningful and fruitful in its true letter and sprit.

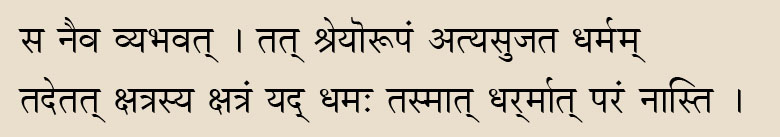

In a society based on democratic socialism, Law should be an effective tool to assuage and uplift the weaker section. Brihadaranyakopanishad which proclaims the supremacy of

Law is as follows:

- Brihadaranyakopanishad, 1:4:14

Which means "Law is the king of Kings, No one is above Law. Law aided by the King enables the weaker to win over the stronger including the king himself."

In other words, law is an effective tool to empower the weaker over mighty and it should not be vice versa and the State should enact laws for the welfare of people at large and cannot inflict injuries on weaker section under the guise of economic reforms.

From conjoint reading of the preamble, Art.14, Art 21 and 39 of the Constitution along with preamble , an irresistible and inescapable conclusion can be drawn that the society based on the principle of socialist and welfare state forms part of Part III rights and cannot be whittled down by statute. So it can easily be concluded that the goal of socialist, welfare State, forms part of Fundamental Rights.

In these legal back drops, the State cannot compulsorily acquire agrarian land of poor farmers and help the corporate giants to amass wealth at the cost of the poor. In majority of cases, agricultural land is the source of livelihood of poor farmers who knows no other job due to their illiteracy and living conditions. Illiterate and under privileged farmers will be thrown to streets, in case of compulsory acquisition of property to help the corporate companies, who can acquire property by using their own funds. The poor farmers will have no opportunity to get white coller jobs or skilled job, as they are uneducated, unskilled and who knows only agricultural work. Depriving their land will amounts to deprival of their livelihood and infringing their freedom of right to work and livelihood. Though the property right is not a fundamental right, in case where agricultural land of poor farmers are snatched for multi nationals, it will amount to deprival of livelihood and right to work; thereby amounts to infringement of fundamental right enshrined under Arts. 14,19 and 21. Here again tillers and farmers are subjected to discrimination and exploitation, for amassing wealth to certain corporate giants, whose sole intention is to make profit and have no public interest or public purpose.

By enacting SEZ ACT, 2005 the world's best democracy has inflicted blows on poverty sticken daridranarayanas, so as to attain the dream of "welfare state" or "Ramarajya".

Be that as it may, I conclude my thoughts by quoting Plato and Gandhiji:

I quote Plato: "I declare that justice is nothing else than that which is advantageous to stronger (V.R. Krishna Iyer, The Dialogues and dynamics in Human Rights in India, P.92)"

"One can withstand the atrocities committed by one individually. But it is difficult to cope with the tyranny perpetuated upon people in the name of people" (Gandhiji, Collected words of Gandhiji Vol. 1. P.204).

* Paper submitted at Bar Council in the Work Shop on 'Security in Society'.

Quick Disposal of Cases

By V.M. Balakrishnan Nambisan, Advocate, Taliparamba

12/05/2008

12/05/2008

Quick Disposal of Cases

(By V.M. Balakrishnan Nambisan, Advocate, Taliparamba)

"Justice delayed is justice denied" is an oft-quoted adage. But justice hurried is justice buried". Can we not have a via media?

In this super-fast world, we seek super-fast justice. In olden days, litigants had enough time to spare for litigations. Touts also promoted its protraction. For them, it is a milching cow. But time has changed. Everybody is busy. We have no time to wait or waste. All of us are in a hurry. Many litigants give up litigation midway for the simple reason of delay. Hence we think of dispensation of quick justice.

Formerly, after filing Vakalath for a defendant, there used to be several month - long adjournments for filing written statements, for framing issues, for summoning witnesses and documents, for examination of witnesses, for arguments etc. etc.

But when the Special List system was introduced, to some extent it quickened delivery of justice. And of late, we started Adalaths - it has two main advantages. Firstly, there will be no appeal and secondly, the litigants who had been fighting tooth and nail, when the case is settled, they shake hands, smile and part as friends (See 2008 (2) KLT SN 2 (C No. 2), T.Vineed v. Manju S.Nair). It is reported that there are about 3.50 lakhs of cases pending in various High Courts in the country. If so, what would be the volume of cases pending in lower courts? And what is the way out to reduce it?

In-Built Mechanism:-

In fact, there is an in-built mechanism in the Code of Civil Procedure (for short CPC) itself to solve the problem. It is easy. The fact is that it is not properly made use of. Some Easy ways:

1) Issue of Summons :- Even at the time of issuing summons to the defendants, the Court shall determine whether it shall be for the defendant to appear and state whether he contests or not and if contests, directing him to file his written statement and documents and also to produce his witnesses if for final disposal (0. 5 Rr. 5 to 8 of C P C). And if either party fails to produce his evidence without sufficient cause, the Court may at once pronounce judgment (0.15 R.4).

Note : Summons is issued not by Judges directly, but by the office staff. They usually don't apply their mind to it. It is therefore advisable to give a short training to them to issue summons on the lines mentioned above.

If the above procedure is followed strictly, very many cases will get terminated even on the very first day of the first hearing.

2) Settlements: Secondly, Courts are mandated to ascertain and record the admissions and denials from each party at the very first hearing and thereafter the court shall direct the parties to settle the matter outside Court through any of the forums provided in S. 89 of C.P.C viz., Arbitration, Conciliation, Adalath or Mediation (O.10 R.1A).

Even in cases wherein the Govt. or a Public Officer is a party to the suit, the Courts are duty-bound to make in the first instance itself every endeavor to assist the parties to reach settlement (0.27 R. 5 B).

But it is found that courts are loathe to do it.

3) Judgment at once when no statement: Formerly, Courts used to grant extensive time for filing written statement as said above. But by amendment in 2002, the time is restricted to 30 days, but upto a maximum of 90 days from the date of service of summons (Order 5 Rule 1, 2nd proviso and 0.8 R.1, 1st proviso). Even this is not strictly adhered to. Some Judges used to insist that application should be filed for granting time beyond 30 days. To a small extent, it is helpful. But there is a lacuna in the law. A defendant who gets 90 days' time for filing written statement, deliberately does not file it but remains ex parte. The court adjourns the case for ex parte evidence of plaintiff to another date, say, some 10 or 15 days thereafter. In the meantime, the defendant files an application to set aside the ex parte order. No time limit is prescribed for it. As such, the defendant can get the ex parte order, set aside any time before the suit is finally disposed of. This makes the 30 to 90 days' period a mere mockery. To overcome this, Court can decree the suit at once adopting the affidavit filed along with the plaint, under 0.7 R.15 as evidence of plaintiff invoking the power under 0.8 R.10 of Code of Civil Procedure. The litigants will then become more vigilant also.

4) Interlocutory applications: The above is applicable only till the parties appear before the court and put in their statements etc. But the protraction begins thereafter. Interlocutory Application (for short I.A.) comes one after another. Each I.A. is a stumbling block in the progress of the case. Sometimes, of course, they are helpful to dispose of the case quickly. But at times, it is retrogressive as well. A clever Judge therefore tries to dispose of the lA's at the earliest. Once it is done, the suit becomes ripe for trial and it can be listed for trial and the parties can expect disposal of their case soon.

5) Bench and the Bar, Co-operation: Apart from the above, for speedy disposal of cases, co-operation of the Bench and the Bar is essential. There must be a congenial atmosphere. To create -it, it is desirable to have occasional joint meetings of the Bench and the Bar, to be presided over by the senior-most member of the Bar. Let there be some sort of interaction on a cup of tea. It will definitely promote harmony which is essential for the smooth functioning of the Court.

There is yet a lot to be discussed on this subject. It is left to the good conscience of the Bench and the Bar of each locality.

Inheritance in Sharia

By S.A. Karim, Advocate, Thiruvananthapuram

12/05/2008

12/05/2008

Inheritance in Sharia

(By S.A. Karim, Advocate, Vanchiyoor, Thiruvananthapuram)

Sharia is the personal law of Muslims. Mulla's Principles of Mohammedan Law and Dr. Tahir Mahmood's Muslim Law of India, are two authorities on the subject. According to sharia, a boy inherits double the share of a girl of the same parents. The theory behind this is that girl is send by marriage, and she becomes member of another family. Boy remains home and he looks' after the parents. So he inherits double. This theory is now dead one. Looking after parents depends on the mentality and culture of the children. What is presumed to the boys can equally be presumed to girls. Law is not expected to discriminate between boys and girls.

Among Hindus and X'ians, there is no such discrimination between boys and girls. They inherit equally. Our Constitution, Art.14, speaks eloquently about equality before law.

"The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the law within the territory of India."

Sharia is under our Constitution. No law survives against the spirit of the Constitution. The same sharia applies in Bangladesh where 90 percent of the population is Muslim. There women organizations have started battle against gender discrimination in inheritance. They demand equal property rights between boys and girls.

Similar is the case with pre-deceased children. If a married man or woman dies before inheritance from one's family, the children of the deceased inherits nothing. While the fortunate survivors inherit more than their due share. Equity demands to inherit the share of the pre-deceased to one's children.

Cultivate the Habit of Reading

By V.R. Venkitakrishnan, Senior Advocate, Ernakulam

12/05/2008

12/05/2008

Cultivate the Habit of Reading

(By V.R. Venkatakrishnan, Sr. Advocate, Ernakulam)

This exhortation from an octogenarian should not be misunderstood as an act of condescension with a patronising attitude. This comes from a person who is completing 60 years at the Bar in a few months. I am tempted to write this because language is not merely a vehicle of thought but a powerful instrument of persuasion which has a decisive effect on the success of a lawyer. I have found to my dismay, many lawyers struggling for words and struggling for apt words when a doubtful proposition or novel proposition in law is attempted to be put forward. There language plays a great part because the nuances in the English language are variegated and attractively colourful. I have often felt that some members of the Bar who are competent and well prepared are not able to put forward their point of view with the compelling elegance of an accomplished lawyer because of his lack of mastery in the language. My readers will pardon me for my attachment to the English language, which whether you like it or not, is a language spoken and known throughout the World. Attachment to English cannot be described as being antinational and unpatriotic. The English language cannot be rejected because it is a foreign language. This language is as much foreign to us as Hindi in South India. We have to learn Hindi with effort as we learn English; Hindi like any other Indian language is soft and sweet and immensely attractive but it is of no use for a lawyer. The South Indian languages like Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam are some of the sweetest languages in the World. But all on a sudden, none of them can be substituted in the place of English. So long as we have the Anglo Saxon System of Jurisprudence and so long as our decisions and precedents are in English, it is difficult to replace English, for years to come. In fact, what keeps India together as one nation is the English language and no one stands in the way of developing his attachment and love to the local languages in India. They are sweet and scintillating but it will take a very very long time before they can become proper substitutes to the English language.

I am happy to tell you that we had a Principal in the St.Thomas College, Trichur, Rev.Fr. John Palokaran, M.A.(English) who advised us to read all the books by certain authors and some books by all the authors. This great Principal said so, so that we will be fairly familiar with all branches of English Literature; Poetry, Drama, Fiction and Prose. Some of us tried to follow this advice to our. great advantage. In fact, while we were in the 8th Standard (Fourth Form) we were introduced to the Panorama of English Literature by the books written by Sir Walter Scott, Charles Dickens and W.M. Thackary. The system then was to go through a chapter and prepare a summary or precis. This we did religiously and absolutely and it paid good dividends. In fact, my favourite book in those days was "The Vicar of Wake-field" by Oliver Gold Smith. This was my Bible and next only to the Bhagavath Gita. There was of course Thomas Hardy who wrote a large number of books on human nature and aspirations. This wide reading helped many of us in our later career in life. Unless one reads enough one cannot write; Dr. Johnson said "I don't want to see a man who has written more than the has read". This will help all lawyers in drafting their pleadings with precision and attraction.

The modern generation need not stick on to all these old authors. There are very many brilliant modern writers even today but one must sit down and acquire the patience to read a book and assimilate the contents. There was in those days two theories, intensive rending and extensive reading; intensive reading meant going meticulously into every sentence of a book, extensive reading is a reading consistent with an attempt to get a general idea of the contents of a book. The reading habit is born with some persons but in the case of others, it can be cultivated and it should be cultivated. My readers will pardon me for this request on my part to insist on compulsory reading. The result will be miraculously edifying and highly gratifying.

You may take it from me that command of the language brings many benefits of forensic eloquence, persuasive skill and an enviable capacity to clarify and convince a court and bring the court to your point of view.

The television and the radio have, to some extent, curtailed the reading habit in all persons; letter writing is an art by itself but it is losing its place because of the E-mail, S.M.S and the computer. There is no substitute for a display of your vocabulary cultivated by extensive and selective reading. Language, it is repeated has got a formidable place in the field of persuasive capacity and persuasion is an important part of Advocacy. With excellent language you can be bold and assertive without being offensive, you carry conviction to an enviable extent and art in language is a supportive force.

There is now a school of thought which indulges in thinking that English language has lost its place and charm. This is far from correct. This language is spoken through out the World and in all the assemblies of the World and listened to with rapt attention. My readers, I hope, will have the patience to read this genuine appeal and imbibe a portion of the same and this is my honest request to improve one's language. Language plays a great part in everybody's life, more so in the life of a lawyer. Consider this honest appeal and let it not fall on deaf ears with any sense of cynicism, it is never too late to learn.