A Case for the Repeal of Rule 6 from The Contempt of Courts

(High Court of Kerala) Rules

By P.K. Suresh Kumar, Senior Advocate, High Court of Kerala, Ernakulam

25/07/2020

25/07/2020

A Case for the Repeal of Rule 6 from The Contempt of Courts

(High Court of Kerala) Rules

(By P.K.Suresh Kumar, Senior Advocate)

A High Court, as envisaged by the Constitution of India is a mighty institution. The founding fathers wanted that court to have all the glory and prestige so as to match its huge role to be played under the constitutional scheme. That is why the Constitution, even before describing who would constitute the court hastened to say through Article 215 that the High Court would be a Court of Record and shall have all the powers of such a court including the power to punish for contempt of itself.

A Court of Record is not defined by the Constitution. But, as the Supreme Court said the expression is well recognized in the juridical world as a court whereof the acts and judicial proceedings are enrolled for a perpetual memorial and testimony and which has power to fine and imprison for contempt of its authority (1991 (2) KLT OnLine 1007 (SC) = AIR 1991 SC2176).Being a Court of Record with power to punish contempt of its authority is the hallmark of a superior court in Anglo Saxon legal system and it was well recognized during the colonial period that the Indian High Courts were such superior courts. It is that superiority that was recognized and retained by the Constitution by way of Art.215.

Article 215, therefore, recognizes and declares the inherent power of a High Court

to punish for the contempt of its authority. The Contempt of Courts Act is only a legisla-tion which regulates the manner in which such power is exercised. As held by the Supreme Court in Supreme Court Bar Association’scase (1998 (1) KLT SN 84 (C.No.85) SC =

AIR 1998 SC 1895)the power to punish for contempt being inherent in a court of record no act of Parliament can take away that power. The Supreme Court further observed that the legislative power cannot be exercised so as to stultify the status and dignity of the Supreme Court or the High Courts though a legislation may serve as a guide for the determination of the nature of punishment or the conduct of the proceedings in that regard.

So, the Contempt of Courts Act is a piece of legislation which acts as a guide to the Supreme Court and the High Courts in the exercise of their authority to punish for contempt. The source of power here is not the statute but is something which is inherent in courts of record as recognized by the Constitution. So, the Act or the Rules thereunder cannot operate in a manner which takes away or undermines the power of the Courts.

The Kerala Rules under the Contempt of Courts Act, however, makes an invasion into the forbidden area by taking away the authority of a single Judge in punishing for the contempt. Art.215 does not make any distinction between a bench consisting of one Judge or two Judges or more. Art.216 says the High Court shall consist of a Chief Justice and such other Judges as the President may from time to time deem it necessary to appoint. So, anyone of them exercising the powers of the High Court is covered by Art.215 too and the power to punish for contempt of its authority is inherent in all Judges who constitute a High Court. However, the Act while regulating the exercise of powers to punish for contempt made a provision through S.18 that criminal contempt shall be dealt with only by a bench consisting of at least two Judges. The Parliament might have thought that criminal contempt being much more serious in nature compared to disobedience to orders and judgments should be considered by a Division Bench. But, in the matter of civil contempt such a condition has not been imposed by the Act. So, it is obvious that the intention of the Parliament is that civil contempt shall be dealt with by any bench irrespective of its strength. Probably, the intention is to facilitate the hearing of matters relating to civil contempt by the author of the judgment itself. The hearing by the author of the judgment, as far as possible, is highly necessary because she/he is the best person to know its spirit and purpose.

But, those who have framed The Kerala Rules under the Contempt of Courts Act seem to think that Single Judges are incapable of dealing with even ‘civil contempt’. Rule 6

of the said Rules reads: “Every proceeding for contempt shall be dealt with by a Bench of not less than two Judges”. A proviso to the said Rule, of course, permits a single Judge to hold a preliminary enquiry in the matter if the judgment or order alleged to be violated is his or hers. But, the single Judge has to post the case before a Division Bench if she/he finds that someone is prima facieguilty of contempt. The moment someone is found to be prima facieguilty of contempt, the single Judge becomes powerless and helpless. This is a very anomalous situation and is not warranted either by the Constitution or the Contempt of Courts Act. I am sure that the great minds which worked behind the promulgation of Art.215 would not have ever dreamt of such a situation.

Rule 6 of the Contempt of Courts (High Court of Kerala) Rules which creates such an absurd situation has to be removed from the Rules. It is inconsistent with Art.215 of the Constitution of India and also inconsistent with the Contempt of Courts Act. S.23 of the Contempt of Courts Act confers power on the Supreme Court and the High Courts to make rules not inconsistent with the provisions of the Act and providing for any matter relating to its procedure. The power is very limited in nature; it can only lay down the procedure and it cannot go inconsistent with the Act. While laying down the procedure it cannot take away a power which a single Judge enjoys by virtue of the Constitutional provision and also as per the Act. As mentioned earlier, the Act insists for a hearing by a Division Bench only in the matter of criminal contempt. So, as per the Act, civil contempt can be dealt with by any bench irrespective of its strength. That position cannot be altered by the Rules which are intended only to provide a procedural form. The villainous Rule 6 is therefore liable to be removed from the statute book without any delay.

To make matters worse, a Division Bench went to the extent of saying that a single Judge did not have power even to summon an alleged contemner. The decision reported in 2014 (1) KLT 147 (Jyothilal v. Mathai)relied heavily on Rule 6 and held that a contempt proceedings begin only when the Division Bench is in seisin of the matter. Rules relating to service of notice and personal appearance etc. were all held to be irrelevant while a single Judge dealing with a contempt case for holding preliminary enquiry. The decision which makes a single member bench all the more powerless is rendered without understanding the larger concepts behind the constitution of a court of record with plenary powers and is definitely retrograde. The decision is liable to be pushed into oblivion and that is possible only by the removal of Rule 6.

By removing Rule 6 and allowing single Judges to handle contempt cases in their entirety would surely enhance the effectiveness in dealing with disobedience to judgments and orders. But, a doubt may arise here as to whether the Chief Justice cannot allot all contempt matters to a Division Bench without the aid of Rule 6. There, my only answer is that the Master of the Roster will act only in consonance with the spirit of Art.215 and will always uphold the dignity of the court.

A Perspective on the Inherent Power of the Court

By O.V. Radhakrishnan, Senior Advocate, High Court of Kerala

18/07/2020

18/07/2020

A Perspective on the Inherent Power of the Court

(By O.V. Radhakrishnan, Senior Advocate, High Court of Kerala)

Judges ought to remember that their office is jus dicere, and not jus dare; to interpret law, and not to make law, or give law. -- Francis Bacon1

The object of this Article is to present a blue-print of jural calculus based on the summation of the settled principles for the exercise of inherent power by the Courts in the adjudication process. The word ‘inherent’ is very wide in itself and means existing and inseparable from a permanent attribute or quality, an essential element, something intrinsic or essential vested in or attached to a person or office as a right or privilege2. Inherent power may signify an authority asserted independent of the Constitution and does not owe its origin to statute. The inherent power is, however, recognized by statutes and may be described as “implied”, “essential”, “incidental”, or “necessary”. It is most often described as “inherent”3. This power is essential to the existence, dignity and operation of a Court. Judicial power vests in Courts and it carries with it those necessary, incidental powers which must belong to them if they are to function as Courts. The power is implied because it is indispensable if the Court is to perform the duties and functions fully and freely and to preserve its dignity, the decorum and order4.

The concept of inherent powers as described in ‘The Inherent Jurisdiction to Regulate Civil Proceedings’ by M.S. Dockray is the foundation for a whole armoury of judicial powers, many of which are significant and some of which are quite extraordinary and are matter of constitutional weight5.I.H.Jacob in his book titled ‘The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Court, Current Legal Problems’6 has rundown the idea on the subject, “In many spheres of the administration of justice, High Court of Justice in England exercises a jurisdiction which has the distinctive description of being called ‘inherent’.”The practical necessity for conceding inherent power to the Court is explained by the Polish Jurist Jerzy Wroblewski -

“There is no need of a Judge where the rule lead everyone, provided no errors are committed, to the same solution, and where correct rule of reasoning from indisputable premises exist. We need Judges when those rules are equivocal when reasoning does not end in a conclusion, but justify a decision”7.

Statutory law responded with legislation on inherent power of the Court specifying its substantive scope of and setting the limits to the Court’s power exercisable in defined and catalogued circumstances is still a desideratum.In this predicament, the Courts have to follow the parameters and the positive indicators laid down in the legal literature particularly, in the binding precedents for invoking inherent power while considering special circumstances of the individual cases. The philosophy of ‘saucing law with justice’ must be the driving force immanent in the exercise of inherent power of the Court.

The Supreme Court is established and constituted under Article 124 and the High Courts are established and constituted under Article 214 of the Constitution of India.

Article 129 of the Constitution proclaims that the Supreme Court shall be a court of record and shall have all the powers of such a court including the power to punish for contempt of itself. Article 215 of the Constitution declares that every High Court shall be a court of record and shall have all the powers of such a court including the power to punish for contempt of itself.

The question whether in the absence of any express provision a Court of Record has inherent power in respect of contempt of subordinate or inferior courts, has been considered by English and Indian courts. In the leading case of Rex v. Parke8Wills, J. observed:

“This Court exercises a vigilant watch over the proceedings of inferior courts, and successfully prevents them from usurping powers which they do not possess, or otherwise acting contrary to law. It would seem almost a natural corollary that it should possess correlative powers of guarding them against unlawful attacks and interferences with their independence on the part of others.”

In Attorney General v. British Broadcasting Corporation9, the House of Lords proceeded on the assumption that a court of record possesses protective jurisdiction to indict a person for interference with the administration of justice in the inferior courts. . . .”

A Seven-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court in re, under Article 143, Constitution of India10 declared that:

“ ..... Besides, in the case of a superior Court of Record, it is for the court to consider whether any matter falls within its jurisdiction or not. Unlike a Court of limited jurisdiction, the superior court is entitled to determine for itself questions about its own jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court approvingly quoted the passage from the decision of the Privy Council in Jairam Das v. Emperor11 hereinafter appearing:

“Prima facie”, says Halsbury, ‘no matter is deemed to be beyond the jurisdiction of a superior court unless it is expressly shown to be so, while nothing is within the jurisdiction of an inferior court unless it is expressly shown on the face of the proceedings that the particular matter is within the congnizance of the particular court”12.

In Delhi Judicial Service Association v. State of Gujarat13, the Supreme Court decided that:

“The English and the Indian authorities are based on the basic foundation of inherent power of a Court of Record, having jurisdiction to correct the judicial orders of subordinate courts. The King’s Bench in England and High Courts in India being superior Courts of Record and having judicial power to correct orders of subordinate courts enjoyed the inherent power of contempt to protect the subordinate courts.”

“The High Court being a Court of Record has inherent power in respect of contempt of itself as well as of its subordinate courts even in the absence of any express provision in any Act. A fortiori the Supreme Court being the Apex Court of the country and superior court of record should possess the same inherent jurisdiction and power for taking action for contempt of itself as well as for the contempt of subordinate and inferior courts.”

A Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Supreme Court Bar Association v. Union of India14, has affirmed that:

“A court of record is a court, the records of which are admitted to be of evidentiary value and are not to be questioned when produced before any court. The power that courts of record enjoy to punish for contempt is a part of their inherent jurisdiction and is essential to enable the courts to administer justice according to law in a regular, orderly and effective manner and to uphold the majesty of law and prevent interference in the due administration of justice.”

“The plenary powers of this Court under Article 142 of the Constitution are inherent in the Courts and are complimentary to those powers which are specifically conferred on the Court by various statutes though are not limited by those statutes. These powers also exist independent of the statutes with a view to do complete justice between the parties. ..... There is no doubt that it is an indispensable adjunct to all other powers and is free from the restraint of jurisdiction and operates as a valuable weapon in the hands of the Court to prevent ‘clogging or obstruction of the stream of justice’.”

In M.M.Thomas v. State of Kerala15 the Supreme Court reinforced that:

“The High Court as a court of record, as envisaged in Article 215 of the Constitution, must have inherent powers to correct the records. A court of record envelops all such powers whose acts and proceedings are to be enrolled in a perpetual memorial and testimony. A court of record is undoubtedly a superior court which itself is competent to determine the scope of its jurisdiction. The High Court, as a court of record, has a duty to itself to keep all the records correctly and in accordance with law. Hence, if any apparent error is noticed by the High Court in respect of any orders passed by it the High Court has not only power, but a duty to correct it. The High Court’s power in that regard is plenary. In Naresh Shridhar Mirajkar v. State of Maharashtra16a nine-Judge Bench of this Court has recognised the aforesaid superior status of the High Court as a Court of plenary jurisdiction being a court of record”.

This issue surfaced again on the case in Asian Resurfacing of Road Agency Private Limited & Anr. v. Central Bureau of Investigation17 the Supreme Court considering the earlier decisions recapitulated the legal position:

“It is thus clear that the inherent power of a court set up by the Constitution is a power that inheres in such court because it is a superior court of record, and not because it is conferred by the Code of Criminal Procedure. This is a power vested by the Constitution itself, inter alia,under Article 215 as aforestated. Also, as such High Courts have the power, nay, the duty to protect the fundamental rights of citizens under Article 226 of the Constitution, the inherent power to do justice in cases involving the liberty of the citizen would also sound in Article 21 of the Constitution.”

In the decision in Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai & Anr. v. Pratibha Industries Ltd. & Ors.18 the Supreme Court ruled that the constitutional courts being courts of record, the jurisdiction to recall their own orders is inherent by virtue of the fact that they are superior courts of record.

The ratio of the above decisions refined and resolved by the Supreme Court is that the Supreme Court and the High Court being the Courts of record possess inherent power to correct the judicial orders of subordinate courts and possess protective jurisdiction for taking action for contempt of itself as well as for the contempt of subordinate and inferior Courts. The Courts of record also possess pleanary power to correct its own orders unless, otherwise prohibited by statute.

The inherent power of the Supreme Court under Article 142 of the Constitution to do ‘complete justice’ is a residuary power, supplementary and complementary to the powers specifically conferred by the Constitution and the statutes. It is a constituent power having transcedental level of application. Prohibitions or limitations or provisions contained in ordinary laws cannot, ipso factoact as prohibitions or limitations on the constitutional powers under Article 142 of the Constitution. Nevertheless, in exercise of the power under

Article 142 of the Constitution the Supreme Court is not expected to pass order in contravention of or ignoring the statutory provisions nor is the power exercised merely on sympathy.19 A Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Supreme Court Bar Association’s case14 has already held that while exercising power under Article 142 of the Constitution, the Court cannot ignore the substantive rights of a litigant while dealing with a cause pending before it. The power cannot be used to ‘supplant’ substantive law applicable to a case. The Supreme Court further declared that Article 142, even with the width of its amplitude, cannot be used to build a new edifice where none existed earlier, by ignoring express statutory provision dealing with a subject and thereby achieve something indirectly which cannot be achieved directly. The power under Article 142 also cannot be used to grant relief on a question not falling within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.20 The High Courts and Tribunals have no similar power.

The inherent power of the High Court in criminal matters which the Court already possessed is preserved and received statutory recognition in Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. What is saved under Section 482 is the inherent power of the High Court to make such orders as may be necessary to give effect to any order under the Code meaning thereby, the High Court’s power to enforce any order under the Code is unaffected by the other provisions of the Code. Section 482 also saves the inherent power of the High Court to prevent abuse of the process of any Court or otherwise to secure the ends of justice. In exercise of the inherent powers vested with the High Court, it is legally obligated to prevent abuse of the process of the Court and to quash a criminal proceeding initiated illegally, vexatiously or being instituted without jurisdiction for the purpose of securing the ends of justice. The Code of Criminal Procedure being an Act made to consolidate and amend the Law relating to Criminal Procedure, the saving of inherent powers of the High Court under Section 482 is limited to matters relating to procedure in criminal proceedings.

In Janata Dal v. H.S. Chowdhary21, the Supreme Court set the scenario of inherent power of the Court:

“Section 482 which corresponds to Section 561-A of the old Code and to Section 151 of the Civil Procedure Code proceeds on the same principle and deals with the inherent power of the High Court. The rule of inherent powers has its source in the maxim ‘Quadolex aliquid alicui concedit, concedere videtur id sine quo ispa, ess uon potest’which means that when the law gives anything to anyone, it gives also all those things without which the thing itself could not exist.

The criminal courts are clothed with inherent power to make such orders as may be necessary for the ends of justice. Such power though unrestricted and undefined should not be capriciously or arbitrarily exercised, but should be exercised in appropriate cases, ex debito justitiaeto do real and substantial justice for the administration of which alone the courts exist. The powers possessed by the High Court under Section 482 of the Code are very wide and the very plenitude of the power requires great caution in its exercise. Courts must be careful to see that their decision in exercise of this power is based on sound principles.”

In Asmathunnisa v. State of Andhra Pradesh & Anr.22, the Supreme Court reiterated that the power under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure is wide but has to be exercised with great care and caution. The interference must be on sound principles and the inherent power should not be exercised to stifle the legitimate prosecution. The Supreme Court quoted with approval the observation of Lord Reid inConnelly v. Director of Public Prosecutions23 that:

“There must always be a residual discretion to prevent anything which savours of abuse of process”, with which view all the members of the House of Lords agreed but differed as to whether this entitled a Court to stay a lawful prosecution.

InDineshbhai Chandubhai Patel v. State of Gujarat24, the Supreme Court did not concur with the approach of the High Court in going into the minutest details in relation to every aspect of the case to quash the FIR and held that the High Court had exceeded its powers while exercising its inherent jurisdiction under Section 482 of the Code. The Supreme Court cautioned that:

“The inherent powers of the High Court, which are obviously not defined being inherent in its very nature, cannot be stretched to any extent and nor can such powers be equated with the appellate powers of the High Court defined in the Code. The parameters laid down by this Court while exercising inherent powers must always be kept in mind else, it would lead to committing the jurisdictional error in deciding the case.”

Relying on the decision in Naresh Shridhar Mirajkar16 a two-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court in M.V.Elisabeth v. Harwan Investment and Trading (P) Ltd25 the Supreme Court elucidated that:

“The High Courts in India are superior courts of record. They have original and appellate jurisdiction. They have inherent and plenary powers. Unless expressly or impliedly barred, and subject to the appellate or discretionary jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, the High Courts have unlimited jurisdiction.”

In a recent decision in Sanjeev Kapoor v. Chandana Kapoor26 the Supreme Court made the legal position explicit ruling that:

“The legislative Scheme as delineated by Section 369 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898, as well as Legislative Scheme as delineated by Section 362 of Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 is one and the same. The embargo put on the criminal court to alter or review its judgment is with a purpose and object. The judgments of this Court as noted above, summarised the law to the effect that the criminal justice delivery system does not cloth criminal court with the power to alter or review the judgment or final order disposing the case except to correct the clerical or arithmetical error. After the judgment delivered by a criminal Court or passing final order disposing the case the Court becomes functus officioand any mistake or glaring omission is left to be corrected only by appropriate forum in accordance with law.”

Inevitably, the inherent power exercisable by the High Court as a Court of record is subject to the express or implied bar in a statute and subject to the appellate power of the Supreme Court. The inherent power of the Court not contemplated by the saving provision in Section 362 of the Code of Criminal Procedure is expressly excluded. It operates as a restraining order forbidding the court from altering or reviewing the judgment after signing or final Order except to the limited extent of correcting a clerical or arithmetical error.

The inherent power of the Court in civil jurisdiction received the statutory confirmation and perhaps, extension by Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure. The above section directing that nothing in the Code shall be deemed to limit or otherwise affect the inherent power of the Court to make such orders as may be necessary for the ends of justice or to prevent abuse of the process of the court, sets the Court free from the rigour of other provisions in the Code for the said avowed goal.

In K.K.Velusamy v. Palanisamy27, the Supreme Court has summarised the scope of Section 151 of the Code explained in several decisions of the Apex Court that Section 151

is not a substantive provision which creates or confers any power or jurisdiction on courts. It merely recognizes the discretionary power inherent in every court as a necessary corollary for rendering justice in accordance with law, to do what is ‘right’ and undo what is ‘wrong’, that is, to do all things necessary to buttress the justice system. The Supreme Court emphasised the need to be doubly cautious by the Courts in exercising the inherent power in the absence of legislative guidance to deal with the procedural situation leaving the exercise thereof on the discretion and wisdom of the individual Judges and that the inherent power cannot be treated as a carte blancheto grant any relief. It has been signalled that the inherent power should be exercised only to meet the ends of justice and to prevent abuse of process of court.

In Mohit Alias Sonu & Anr. v. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr.28, the Supreme Court handed down the ruling:

“The intention of the legislature enacting the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Code of Civil Procedure vis-a-visthe law laid down by this Court it can safely be concluded that when there is a sepecific remedy provided by way of appeal or revision the inherent power under Section 482 Cr.P.C. or Section 151 C.P.C. cannot and should not be resorted to.”

In the recent decision in SCG Contracts (India) Private Limited v. K.S. Chamankar Infrastructure Private Limited & Ors.29, the Supreme Court following the decision in Manohar Lal Chopra’scase asserted that:

“Clearly, the clear, definite and mandatory provisions of Order 5 read with Order 8,Rules 1and 10 cannot be circumvented by recourse to the inherent power under Section 151 to do the opposite of what is stated therein.”

The inherent power of the Court to make such orders as may be necessary for the ends of justice or to prevent abuse of the process of the Court is saved under Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure. The power saved under Section 151 relates to matters of procedure. The Writ Proceedings are not ‘proceedings’ within the meaning of Section 151 of the Code and are not governed by the Code by force of the specific statutory clarification contained in the Explanation under Section 141 of the Code that the expression “proceedings” does not include any proceeding under Article 226 of the Constitution.

The power cognizant of under Section 151 of the Code of Civil Procedure relates to matters of procedure and cannot encroach upon the substantive rights of the parties. It does not confer any power on the civil courts. It only clarifies that the power to make such orders as may be necessary for the ends of justice and to prevent abuse of the process of court is not fettered by the other provisions of the Code. A Court cannot exercise inherent power to do that which is prohibited by the Code or in direct contravention of the provisions of the Code. The above provision does not grant power to deal with matters which are excluded from its cognizance. If there are express provisions exhaustively covering a particular topic, no inherent power shall be exercised in respect of the said topic. Inherent power cannot be resorted to as a blanket power but only for the felt necessities of securing the ends of justice and to prevent abuse of process of Court as a pervasive principle.

The jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution of India for issuing writ of certiorari is limited to seeing that the judicial or quasi-judicial tribunal or administrative body exercising quasi-judicial powers do not exercise their powers in excess of their statutory jurisdiction, but correctly administer the law within the confines of the statute creating them or entrusting those functions to them.

In Nagendra Nath Bora & Anr. v. Commissioner of Hills Division and Appeals, Assam & Ors.30, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court declared that one of the grounds on which the jurisdiction of the High Court on certiorari may be invoked, is an error of law apparent on the face of the record and not every error either of law or of fact, which can be corrected by a superior court, in exercise of its statutory powers as a court of appeal or revision. It has been further held that certiorari is not meant to take the place of an appeal where the statute does not confer a right of appeal. Its purpose is only to determine, on an examination of the record, whether the inferior tribunal has exceeded its jurisdiction or has not proceeded in accordance with the essential requirements of the law which it was meant to administer. Mere formal or technical errors, even though of law, will not be sufficient to attract this extraordinary jurisdiction.

In State of Andhra Pradesh v. Chitra Venkata Rao31, the Supreme Court ruled that:

“The jurisdiction to issue a writ of certiorari under Article 226 is a supervisory jurisdic-tion. The Court exercises it not as an Appellate Court. The findings of facts reached by an inferior court or Tribunal as a result of the appreciation of evidence are not re-opened or questioned in writ proceedings. An error of law which is apparent on the face of record can be corrected by a writ, but not an error of fact, however grave it may appear to be.”

Inevitably, the High Court issuing a writ of certiorari acts in exercise of supervisory and not appellate jurisdiction. In certiorari, the High Court is to determine, on examination of record, whether the inferior tribunal exceeded its jurisdiction or proceeded not in accordance with the essential requirements of law which it was meant to administer. It merely demolishes the order which it considers to be without jurisdiction or palpably erroneous and does not re-hear the case on the evidence or substitute its own findings. The remedy of certiorari is to keep the inferior courts in check by quashing decisions taken without, or in excess of jurisdiction; and quashing also for intra vireserror of law apparent on the face of the record, and quashing decisions tainted by fraud or perjury. Necessarily, resort to inherent power has little or no scope for the grant of certiorari.

A Concluding Caveat

The role of the High Court in judicial review proceeding is to ensure that statutory powers are not usurped, exceeded or abused and that duties owed to the public are duly performed. Logically, the use of inherent power is beyond the purview of the judicial review proceedings. Be it writ of certiorari or supervisory jurisdiction of judicial review, invoking inherent power is an officious encroachment, at once procedurally ultra vires. To bring the inherent power into play has raison d’etreonly if it is exercised to prevent abuse of the process of the court or to secure the ends of justice. Judicial power is a public trust and the inherent power should be put into use by the courts to do justice between the parties and not to act as a superpower unlimited. Call into use inherent power by way of adhoc procedural activism by Judges32 resulting from the lack of coherent limits on judicial power in the discharge of supervisory jurisdiction of judicial review obviously, is an unwarranted arrogation of authority by the judiciary.

Foot Notes

1. “Of Innovations”, The Works of Francis Bacon, v. XII, 1857-74 (M. Scott ed.1908).

2. Concise Oxford English Dictionary (2002).

3. See Dowling. The Inherent Power of the Judiciary, 21 A.B.A.J. 635 (1935).

4. Board v. Thomson 7 Ind. 265 (Semble) (Physical conditions).

5. M.S. Dockray - “The Inherent Jurisdiction to Regulate Civil Proceedings”(1997) 113 L.Q.R.120.

6. I.H.Jacob - ‘The Inherent Jurisdiction of the Court, Current Legal Problems’ (1970). Vol.23, P. 23.

7. Jerzy Wroblewski, The Judicial Application of Law ed. by Zenon Bankowski and Neil Mc Carmack(Kluwer Acadmic Publication-1992) at p.315. The book is the English version Jerzy’s, major polish work-Sadowe Stoswaria Prawa.

8. Rex v. Parke (1903) 2 K.B. 432, 442: (1900-3) All ER Rep.721).

9. Attorney General v. British Broadcasting Corporation ((1980) 3 All ER 161).

10. -- In Re, under Art.143, Constitution of India (AIR 1965 SC 745 at page 789, para 138).

11.-- Jairam Das v. Emperor (72 Ind App.120: AIR 1945 PC 94).

12.-- Halsbury’s Laws of England, Vol.9, P.349.

13.-- Delhi Judicial Service Association v. State of Gujarat (1991 (2) KLT OnLine 1007 (SC) =(1991) 4 SCC 406), paras 26 and 31.

14.-- Supreme Court Bar Association v. Union of India (1998 (1) KLT SN 84 (C.No. 85) SC =(1998) 4 SCC 409), paras.12, 21 and 47.

15.-- M.M.Thomas v. State of Kerala (2000 (1) KLT 799 (SC) = (2000) 1 SCC 666) para.14).

16.-- Naresh Shridhar Mirajkar v. State of Maharashtra (1966 KLT OnLine 1204 (SC) =(AIR 1967 SC 1).

17 Asian Resurfacing of Road Agency Private Limited & Anr. v. Central Bureau of Investigation,

(2018 (2) KLT 158 (SC) = (2018) 16 SCC 299),para 54 at p.333.

18.-- Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai & Anr. v. Pratibha Industries Ltd. & Ors.

(2019 (1) KLT OnLine 3231 (SC) = (2019) 3 SCC 203), para.10).

19.-- Manish Goel v. Rohini Goel (2010 (2) KLT Suppl.66 (SC) = (2010) 4 SCC 393) para.19.

20. State of Karnataka v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2000 (1) KLT OnLine 937 (SC) = (2000) 9 SCC 572).

21.-- Janata Dal v. H.S. Chowdhary (1992 (2) KLT OnLine 1017 (SC) = (1992) 4 SCC 305),paras 131 and 132).

22.-- Asmathunnisa v. State of Andhra Pradesh & Anr. (2011 (2) KLT SN 22 (C.No.30) SC = (2011) 11 SCC 259).

23.-- Lord Reid in Connelly v. Director of Public Prosecutions (1964 AC 1254: (164) 2 WLR 1145: (1964) 2 All ER 401 (HL).

24.-- Dineshbhai Chandubhai Patel v. State of Gujarat (2018 (1) KLT OnLine 3003 (SC) = (2018) 3 SCC 104) at para 33.

25.-- M.V.Elisabeth v. Harwan Investment and Trading (P) Ltd.(1992 (2) KLT OnLine 1002 (SC) = (1993) Supp (2) SCC 433).

26.-- Sanjeev Kapoor v. Chandana Kapoor (2020 (2) KLT 267 (SC)) para.18.

27.-- K.K.Velusamy v. Palanisamy (2011 (2) KLT SN 19 (C.No.27) SC = (2011) 11 SCC 275, para 12.

28.-- Mohit Alias Sonu & Anr. v. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr.(2013 (3) KLT SN 30 (C.No.32) SC = (2013) 7 SCC 789),para.32.

29.-- SCG Contracts (India) Private Limited v. K.S.Chamankar Infrastructure Private Limited & Ors.(2019 (1) KLT OnLine 3040 (SC) = (2019) 12 SCC 210), para.16.

30.-- Nagendra Nath Bora & Anr. v. Commissioner of Hills Division and Appeals, Assam & Ors.

(1958 KLT OnLine 1301 (SC) = AIR 1958 SC 398), paras 24 and 26.

31.-- State of Andhra Pradesh v. Chitra Venkata Rao (AIR 1975 SC 2151), para 23.

32. See Elliot, Supra note 29 at 309 (emphasis in original).

Placing the Mirror ......

By K. Krishna kumar, Advocate, Ottappalam

11/07/2020

11/07/2020

Placing the Mirror ......

(By K.Krishnakumar, Advocate, Ottapalam)

“VAKEELE .......” Most of the advocates belonging to the fraternity would have the opportunity of being called, addressed and mentioned so. After completing the Law-Degree or its higher studies, one enters into the profession. As is the practice, internship – enrolment etc. would make you an Advocate! Thereafter you are known to be a lawyer, Advocate and called as Vakil or Vakeel by your natives etc. You consider it to be a privilege and with pride, you answer the call of ‘Vakeele’ from then onwards.

Are you a Vakeel or an Advocate? Is there a difference between these two? Once a Senior Advocate remarked: All Advocates are Vakils but all Vakils are not Advocates. Why is it so? As on today, can a person who is a Vakeel/Vakil and claim himself to be an Advocate legally? The Law says ‘No’ an emphatic ‘No’! Why is it so?

This article is an attempt to know about a Vakeel/Vakil in India and the transformation of Vakil to an advocate.

Vakil – Vakalathnama:

Vakil or Vakeel is an Urdu word which means an Agent, one who represents. It was a distant synonym of mukthiar. A Vakil of earlier era, was appointed by a person when

he/she found that he requires that person to act, perform, represent him on his behalf in the conduct of a matter, a case or whatsoever.

It was in 1672 that the first British Court was established at Bombay by Governor General Augier. Under a Charter granted by Queen Elizabeth, on 31-12-1600, the British had incorporated East India Company which was managed by Court of Directors (1 Governor and 24 Directors). This Company Court could make laws, ordinances etc. and set penalties and was instrumental in setting up new legal system in India.

There were the Court of Sudder Dewany Adawlat, Provincial Courts, City or Zilla Courts and High Courts which finally paved way for the Supreme Courts.

Under Section 8 of Regulation VII of 1793, a client who desired to have a vakeel, had to pay the retaining fee of four annasto his pleader and execute vakalutnamahin favour of his pleader, vesting him with the powers mentioned in that section. Payment of the retaining fee together with the vakalutnamahcreated the rights and liabilities of the pleader, making him answerable for all such matters.

But a revolutionary change happened in 1814. As per Regulation XXVII of 1814, Section 21, the Vakeel’sretaining fee of four annaswas abolished and the vakalutnamah, almost of the present form was introduced. Section 21 runs as follows: “When a party in a cause, may be desirous of retaining a vakeel for the prosecution or defence of any civil suit, he shall not be required to pay such Vakeel the retaining fee of four annas heretofore prescribed, but he shall execute to him a vakalutnamah, constituting his pleader in the cause, and authorizing him to prosecute or defend the suit, and further binding himself to abide by and to confirm all acts such pleader may do or undertake in his behalf in the cause, in the same manner as if such party had been personally present and consenting. The party is to attest the instrument with his seal or signature, or with his mark if he cannot write, in the presence of two credible witnesses, who are likewise to attest it in the same manner, and who are to attend the court and prove the vakalutnamahin all cases in which it may be judged requisite.” The fee for presenting miscellaneous petitions and applications continued to be four annas.

Section 20 of Regulation XXVI of 1814 authorised the pleaders to receive fees for giving legal opinions. If the pleader giving the opinion was attached to the Court of Sudder Dewany Adawlat, he was entitled to a fee of 24 Rupees. If he was attached to any of the Provincial Courts, he was entitled to a fee of 16 Rupees; if attached to a city or Zilla Court, than he was entitled to a fee of eight rupees only. But if the pleader, giving his opinion had accepted a vakalutnamah, he was not allowed to receive such fee. The scale of fees mentioned so was abolished by Section 9 of Act I of 1844, under which pleaders were authorized to settle by private agreement, and to receive the remuneration to be paid for such matters.

Under Sections 2 and 5 of Regulation VII of 1793 as also Section 3(3) of Regulation XXVII of 1814, only Hindus and Mohammedans were admitted as Vakeels.Till 1846, this was the rule. But it was removed by Section 4 of Act I of 1846 which enacted: “the office of pleader in the Courts of East India Company shall be open to all persons whatever nation or religion, provided that no person shall be admitted as a pleader in any of those courts unless he have obtained a certificate in such a manner as shall be directed by the Sudder Courts, that he is of good character and duly qualified for the office, any Law or Regulation to the contrary withstanding.”

It was also provided in this Act that the parties employing authorized pleaders should be at liberty to settle with them by private agreement the remuneration to be paid for their professional services, and it would not be necessary to specify such agreement in the vakalutnamah. [Act 1 of 1846, Section 7(1)]. Under Section 5 of Act I of 1846 the right of Barristers of any of His Majesty’s Courts of Justice to plead in all courts was recognized. (Also see Section 3, Act XX of 1853). But the Barristers and Attorneys, while pleading before any Court of the East India Company were not required to produce certificate of character.

When Act XVIII of 1879 was passed, the rules as to the qualification, etc. of pleaders (excluding the Vakilsof the High Court) and mukhthiers were framed by the High Court under Section 6 of the Act, 1879. To facilitate the ascertainment of qualifications mentioned therein, the local Government, appointed persons as examiners, from time to time, to make regulations for conducting such examinations. The Chief of Revenue Authority was conferred with powers to make rules as to qualifications etc., of revenue agents or mukhthiers.

Thus it was clear that none but those who secured certificate of good moral character were admitted as vakeels and pleaders, and they could be debarred for moral delinquencies. This part of above-mentioned rules were approved and adopted in the rules under the Legal Practitioners Act (Act XVIII of 1879).

Under Section 5 of Regulation VII of 1793 pleaders were to be selected from amongst the students of Hindu College at Benares and the Mohammedan College at Calcutta. If those colleges did not furnish sufficient number of pleaders, the Sudder Devany Adawlut could admit any other persons provided they were Hindus or Mohammedans and men of good character and liberal education. After universities were established holders of University Law Degrees were admitted as Vakeels of the High Court or rather that side of the High Court which represented the old Sudder Dewany Adawluts. Vakeels were never allowed to practice in the “King’s Court” i.e., the old Supreme Courts later which became the original side of the High Courts. Persian was followed as the Court language and it later on paved way to English Language. The vakeels were allowed to practice before Company’s Courts, but not before the King’s Court, i.e., the Supreme Court.1

Advocate – Ordinary & Senior !

The Advocate’s Act (Act 25 of 1961) was promulgated on 19th May, 1961 and the earlier Act – The Legal Practitioners Act, 1879 and such other laws were thereby amended and consolidated.

A legal practitioner as defined under Section 3 of the Act 1879 was: means an advocate, Vakil or attorney of any High Court, a pleader, mukhtar or revenue – agent. The legal Practitioners Act also recognized ‘touts’. A tout was a person – who procures, in consideration of any remuneration moving from any legal practitioner, the employment of the legal practitioner in any legal business; or who proposes to any legal practitioner or to any person interested in any legal business to procure, in consideration of any remuneration moving from either of them, the employment of the legal practitioner in such business [Section 3(a) of Act, 1879).Every High Court, District Judge, Sessions Judge, District Magistrate and Presidency Magistrate, every Revenue Officer not below the rank of a Collector of a District and the Chief Judge of every Presidency small cause Court was to frame and publish the lists of persons proved to their or his satisfaction or to the satisfaction of any subordinate Court as provided in the section, by evidence of general repute or otherwise, habitually to act as touts, and such courts were given authority ‘to alter and amend such list of touts from time to time’. But the Advocates Act, 1961 did not define or envisage any provisions regarding touts. The Act 25 of 1961 defined an Advocate as per Section 2(1)(a) “advocate” means an advocate entered in any roll under the provisions of this Act and a ‘legal practitioner’ vide Section 2(1)(i) – “legal practitioner” means an advocate or Vakil of any High Court, a pleader, mukthar or revenue agent. But a person who is not an Advocate cannot represent a party to a proceeding as of right, but only after obtaining permission of the Court.

The recommendations of the All India Bar Committee made in 1953 and the Law Commission on the Judicial Administration reforms paved the way for Act 25 of 1961 i.e., the Advocate’s Act 1961. It replaced the Indian Bar Councils Act, 1926 and all other laws on the subject. The statement and objects and Reasons (SOR) laid down that the chief function of a lawyer was administration of justice. It also highlighted the legislative intention that the Act was to amend and consolidate the law relating to legal practitioners i.e., to integrate the Bar as a single class of legal practitioners to be known as Advocates. But at the same time, as per Section 16, the Act classified advocates as ‘Senior and other Advocates’.

Advocate, the Bar, Bar Council became important terms regarding legal profession.

The Bar & Advocates

The whole body of attorneys and counselors or the members of the legal profession collectively, are figuratively called the Bar from the Place which they usually occupy in the Court. Advocates are thus distinguished from the Bench which term denotes the whole body of judges. During the trial of a cause, the space occupied by the judges, counsel, jury and others concerned in the trial and the general public is separated by a partition or railing running across the court-room and this is called Bar.2

Our Apex Court observes: The Bar is not a private guild, like that of ‘barbers, butchers and candle-stick makers’ but, by bold contract, a public institution committed to public justice an pro bonopublic service. The grant of monopoly licence to practice law is based on three assumptions: (1) there is a socially useful function for the lawyer to perform. (2) A lawyer is a professional person who will perform that function and (3) His performance as a professional person is regulated by himself and more formally, by the profession as a whole. The central function that the legal profession must perform is nothing less than administration of justice. The Advocates Act creates an all India Bar with only one class of legal practitioners, namely advocates, who of course, are classified as Senior Advocates and other Advocates!”3

Senior & other Advocates:

An ordinary advocate belongs to the category of “other advocates”, and such advocates become a ‘senior advocate’ as per Section 16(2) of the Advocates Act, 1961. Only the Supreme Court or a High Court have these two classes of Advocates. As per Section 16(2) an Advocate may, with his consent, be designated as a senior advocate if the Supreme Court or a High Court is of the opinion that by virtue of his ability, ‘standing at the Bar, or special knowledge or experience in law’, the advocate deserves such a distinction.

A Senior Advocate has a right of pre-audience in a Court of Law.

The High Court of Kerala has framed Rules under Section 16(2) of the Advocates Act, 1961 setting out the method by which ‘other advocates’ get transformed to ‘Senior Advocates’.

Rule 1 High Court can designate an Advocate or Senior Advocate if that Advocate by virtue of the ability and standing at the Bar deserves such distinction. Standing at the Bar explained as: the position of eminence attained by an Advocate at the Bar by virtue of his seniority, legal acumen and high ethical standards maintained by him, both inside and outside the court.

Rule 2 Three modes of sponsorship to become Senior Advocate:

(i) by the Chief Justice or any of the Judges of the High Court

(ii) by any two Senior Advocates

(iii) by an application made by the advocate desiring to be designated as such.

If an Advocate is to be considered other than on his own application, the court must have the concerned Advocate’s consent along with the proposal.

Rule 3 Those who are to be designated as senior ..... must complete 45 years of age and actually practiced as Advocate for not less than 15 years. In reckoning 15 years, the service as a Judicial Officer will also be considered.

Rule 4 The designated should be an Income Tax Assessee for the ten preceding years and his annual gross income from the profession should be about `2 lakhs for the last 3 years.

Rule 5 Relates to the application – format.

Rule 6 The proposal’s consideration at the Judge’s meeting – two third of the Judges present favouring the designation by secret ballot.

Rule 7 An unsuccessful applicant debarred from applying to seniority for the next 2 years.

Rule 8 Undoing designation of Senior Advocate – procedure regarding.

Time and again, the conferring or denial of senior advocate status has resulted in legal battles. The transformation of ‘other advocate’ to ‘Senior Advocate’ was rather compared to the Barrister getting transferred to a Queen’s Counsel (QC) as under the English Legal system. The method and procedure of voting was subjected to legal scrutiny by our High Court, when a learned counsel felt aggrieved over the reluctance of judges to confer him the favour of becoming designated as a Senior Advocate. Abstention during voting of Judges was considered to be a ‘NO’ vote in this case4 And finally, the court remarked: “But, legal nuances apart, litigation for designation robs the advocate of the gravitas the designation demands.”

CONCLUSION:

Therefore next time when you are called: Vakeele....., while you are accepting a vakalath and finally dreaming of being designated as ‘Senior Advocate’....., think of the evolution! Because the society believes you as a legal professional competent to discharge such duties. When we are skilled in our profession, we are supposed to know our evolution too. And it is always said that a person who is skilled in his profession would be believed – “Cullibet in sua arte perito est credendum !”.

Foot Note

1. Courtesy to the Article: The Annals of the Bengal Bar – Calcutta Law Journal – Volume XIX – No.1 by B.K. Acharya

2. P. Ramanatha Aiyar – Concise Law Dictionary – page 112 – 3rd Edition – 2005.

3. Bar Council of Maharashtra v. M.V. Dabholkar (AIR 1995 SC 691).

4. P.B. Sahasranaman v. Kerala High Court (2017 (4) KLT OnLine 2088 = AIR 2017 Ker.174).

Covid 19 Forced Vacation – Some Random Thoughts

By P.B. Menon, Advocate, Palakkad

10/07/2020

10/07/2020

Covid 19 Forced Vacation – Some Random Thoughts

(By P.B. Menon, Advocate, Palakkad)

When a building is let out to a tenant, which is the law which govern the same? T.P. Act or Contract Act or both

Does such letting out of a building on rent a lease as defined in S.105 T.P Act. True it involves a transfer of a right to enjoy such building, but the question is as to whether a legal estate, which is capable of alienation or a marketable interest is created, as in the case of an ordinary lease u/S.105 of T.P.Act. Is it a right or interest that is created in letting out a building. Of the two which transfer has a larger or higher import, a transfer of an interest or a transfer of a right. Is the so called right to possess and enjoy a building on rent a tangible property which has existence in law, which is the correct legal expression to be used when a building is given on rent to a tenant, let out or leased out. Even under the Kerala Act 2/65, the right of the tenant is made heritable but not alienable. Is he a tenant or lessee. Is not their relationship as landlord and tenant; really are they lessor and lessee. One will find a reference in AIR 1976 SC 2229 which hold that the contractual tenant has an estate or property in the subject matter of tenancy and hereditability is an incident of the tenancy, but the decision does not state that it is alienable too.

I strongly feel that when a building is let out on rent, they are governed solely by the Contract Act and not by T.P.Act and their relationship is that of landlord and tenant and not lessor and lessee and no legal estate is created in favour of the tenant so as to make it transferable or marketable as a tangible property in his hands.

Really does Section 106 T.P. Act come into the picture. I think not. True, before eviction is sought, there should be termination of landlord – tenant relationship and for that a notice may be necessary but it is under the common law and not under T.P.Act in areas where the Rent Control Act is not applicable.

A lease under Section 105 T.P. Act creates a leasehold in favour of the lessee which is marketable and alienable, besides being heritable and such lease has to be terminated by issuing a notice u/S.106 of T.P.Act. Both T.P. Act and Contract Act comes into play governing action relating to such leases.

Can an illiterate be a attesting witness to a Will

The Indian Succession Act 1925, Section 63(a) states that a testator shall sign or affix a mark to the will etc., i.e., signature or mark.

When we come to S.63(c) it states that an attestor has to sign the Will i.e., he cannot make a mark.

So can an illiterate who does not know how to read and write be an attestor.

Suppose he knows only to write his name which is his signature, but still an illiterate, does he qualify himself to be an attestor within the meaning of S.63(c) of the Act.

Section 63 speaks of a “mark.”

Is LTI a mark or is it an impression of one’s thumb.

Have you ever seen a document like sale deed or any other deed or Will which is registered by an illiterate executants affixing his left thumb impression in the bottom of each of the pages of the document so executed except before the concerned Sub Registrar; only ‘mark’ will be seen in token of execution at the bottom of each page. What is the correct legal position.

Is a child in the womb, a living person

Does the theory of right by birth depend upon actual birth of a child.

Suppose the wife is pregnant at the time of the death of her husband and his assets have to be shared among his legal heirs, before the birth of the child or after the birth of the child, how will the shares calculated.

Under Section 7 and 8 and not in Section 6 Act 30/56 speaks of persons living. See Section 8 of Act 30/76 also.

Legally can we ignore a child in the womb of the mother in calculating the shares in a partition suit.

In older days in a partition suit of a Marumakkathayam tarawad, a child conceived in between plaint and written statement was entitled to a share.

Scope of Section 109 Indian Succession Act

Under Section 109 of the Indian Succession Act 1925, a testacy in favour of a prede-

ceased son was saved without lapse in cases where the lineal descendents of the predeceased son exists.

In the partition suit to be followed, are the widow and mother of the predeceased son who are his legal heirs under the Hindu Succession Act can share the assets along with the lineal descendents.

It is the lineal descendents who save the estate from being lapsed and not the existence of legal heirs of the pre-deceased son. They saved the estate from lapse for the sake of themselves or for others also.

Effect of Amendment of Hindu Succession Act by Kerala in 2015 of Section15

As regards Section 15, Hindu Succession Act 1956, the same is amended by the Kerala Act with effect from 2015 by introducing a new clause as S.15(2)(C), which states that any property inherited by a female Hindu from her predeceased son shall devolve not upon the other heirs referred to in sub-s.(1) in the order specified therein but upon the heirs of the pre-deceased son from whom she inherited the property.

So the question is as to whether the said mother has a life estate or absolute estate.

In order that such share, mother inherited should go to the heir of the predeceased son only, she must hold it as a life estate holder.

On the other hand if what is intended is absolute estate, unless it is available at the time of her death to be devolved upon the legal heirs of the predeceased son, the same will be lost to them.

What actually is the intention of the legislature when this change was brought about is not clear.

Has the draftsman failed in his duty as usual.

As stated by Fancis Banian, the well known draftsman, “I am the parliamentary draftsman, I compose the country’s laws and for half of the litigations in the country I am undoubtedly the cause”.

Civil Appeal against judgment and not decree – effect

I strongly feel as a Trial Court lawyer that the 2002 Amended C.P.C. is the worst, we ever had even though uphold the validity of the same by the Apex Court in the Salem Bar Associationcase.

Under the amended code an appeal memorandum should be accompanied by the judgment under appeal and not decree. So decree is not before the Appellate Court.

When an appeal is filed without a decree copy, the office cannot verify as to whether such appeal is to be filed before that Court or the High Court. True in CMAs, the order produced will not show the suit valuation which is necessary to decide the form of appeal.

Suppose the decree drafted in pursuance to the judgment is not in conformity with the judgment or subsequently the decree is amended after filing of the appeal and because of amendment a party is aggrieved, what is the remedy open to him. Several situations may arise depending upon the circumstances. How can one challenge the decree as occasion demands, when such decree is not before the appellate court. Suppose the appellate court holds that the decree needs correction, alteration or amendment how can the appellate court remedy the defect as such decree is not before the court.

The C.P.C. as it stands with the amendment in 2002 speaks of an appeal against a decree which takes in deemed decree as well.

In a civil case, what is very significant and important is the culmination of the suit in a decree which is either declaratory or executable and it is on execution of a decree that a party gets complete relief. Such a decree is dropped out by amendment of certain provisions from C.P.C.

Law Journal reports senior counsel

I fully endorse the view of Senior Counsel R.K.Jagadeesan Nair, when he states in his article “ratio decidendi”to the effect that it is better not to report, all the cases wherein settled law is reiterated over again and again, unless a case lays down, something new to be followed by subordinate courts.

Why not the judgments be short and brief that too in simple language as in Privy Council decisions, a brief facts, evidence, reasoning based on law and conclusion so that on reading the judgment one may understand what is decided.

A party is solely concerned with the result and the reasoning behind it and the lawyer is interested in the law laid therein.

Except adding pages to the Law Journals no useful purpose will be served by such reporting of all such cases reiterating the earlier view and law reporters have to play a significant part in this respect.

Marriageable age of girls v. Parental Authority

In view of parental authority should not the law relating to the age of girls for marriage be amended at least as completed 21 years in cases when the marriage is not arranged by parents of the parties or with their full approval and consent or on written permission of the parents of either party to the marriage.

A girl upto the age of 21 is in an adolescent stage; her mind will be weak and vulnerable as stated by the Apex Court. She will not be able to take a matured decision about her future life by entering into a marriage alliance. School/college campus love are all mutual fascination depending on physical beauty, charm, body language, behavior, dress etc., of either party and the surrounding circumstances. One need not try to find out various reasons for that for every day we come across such instances taking place. Hence I feel that to put a check on that an amendment of the marriageable age of a girl should be raised to at least completed 21 years depending upon the circumstance.

Will the civil courts survive for long – I think not

We are now passing though an age of settlements in order to avoid docket explosion. Evidently it was thought proper because of mounting up of litigations in courts.

Section 89 C.P.C. is introduced by 2002 amendment; mediation centers have come into existence. Lok Adalats also play their part.

Now we have come to a stage when all civil disputes are to be settled hereafter by mediation and conciliation, only if they fail a civil court need try a case.

In that process what happens; the civil law will disappear. Civil law will have no role to play. When matters have to be settled in one way or other by alternative disputes forums etc. Where is the scope for civil law. Formerly there was provision for arbitration in cases there is a clause for arbitration in the concerned deed.

I am certainly not against settlement at all, probably my office stands top most in reporting settlements in courts. I strongly feel that it is certainly good for litigants coming to court to settle matters rather than fight.

I am concerned only about as to what will happen to civil law. Even now if I say that good civil lawyers are wanting and are few at various levels from Munsiff Court to Supreme Court I am sure that I may not be wrong. Their number is dwindling day by day.

What I find is that young lawyers who join the profession, prefer criminal courts as they will certainly get a few sum of money to put in their pockets every day which is not the position if one comes to civil side, where you have to wait.

In olden days a green horse joins an office to learn and pick up rudiments of law, but at present they come as assumed ‘full fledged lawyers” without gaining experience from any office of a senior and for that a criminal court is a better field.

Advice is seldom welcome I know, but still, I take this opportunity to advise my young friends coming to the profession to join a senior’s office as well as to attend court proceedings by remaining in courts for the same will give you a working knowledge of our system. Law Books will guide you, but practical knowledge comes from the other two sources which are really important to become a successful lawyer, be on the civil or criminal side.

Power of attorney – registered or authenticated that is required for

registration of a document executed by a power of attorney holder

Registration Act and the Rules specify that what is needed is not registered one but an authenticated power of attorney. A registered power of attorney is useless in that regard.

Let us see the concerned provision of law in the Registration Act and the Rules, leave alone the case law.

We shall begin with Section 32(C) Registration Act “by the agent of such a person, representative or assignor, duly authorized by power of attorney executed and authenticated in the manner hereafter mentioned.

Then what Section 33 stipulate is

1) for the purposes of Section 32 the following powers of attorney shall alone be recognized, namely:

A power of attorney “executed and authenticated” as the case may be:

If the principal is within India execution and authentication by the Registrar and Sub Registrar concerned.

If outside India, executed and authenticated by a Notary Public or any Court, Judge, Magistrate, Indian Consul or Vice Consul or representative of the Central Govt.

So when a principal is within India, can a Notarised Power of attorney be used for the purpose of S.32 to register a document?

Now let us come to Rules.

Chapter X deals with powers of attorney under Section 33.

Rule 57 says how the Sub Registrar has to authenticate a power of attorney and the form is prescribed.

Rule 60 prescribes 1) for authentication, 2) for registration and 3) for both authentication and registration of a power of attorney and as to what the Sub Registrar is expected to do in each case.

Rule 61 is very significant when it states that a power of attorney may be registered like any other instrument, but it is not valid for registration purposes unless authenticate. The said rule also provides that the Sub Registrar is obliged to inform the principal about the destination between the two, registration and authentication, in case of need.

Rule 62 further makes the position clear when it states that when registering officer is authorized to authenticate those powers of attorney which are executed for registering purposes, shall refuse to authenticate a power of attorney unconnected with registration.

Now let us see Section 85 Evidence Act relating to presumption of such powers of attorney. The wording used is very significant.

“The Court shall presume that every document purporting to be a power of attorney and to have been executed before and authenticated by a Notary Public etc.

The presumption applies only to Section 33(C) category of powers of attorney where mere production is sufficient proof. But as regards a merely registered power of attorney no presumption nor its mere production proof.

What is the net result? Only an authenticated power of attorney can be used to execute and register a document before a Sub Registrar and not a Regd. power of attorney, depending upon as to whether the principal is within India or outside India.

But what is taking place every day is Sub Registrar’s Office is quite the opposite of what the law stipulates.

Incidentally may I refer to another matter connected with this.

When a power of attorney executed and authenticated outside India by the concerned Embassy, it cannot really be used as such for the same has to be validated, by getting it stamped u/S.18 of the Kerala Stamp Act with Kerala stamp within 3 months of being received in India before it could be used as evidence. See 2017(3) KLT 989.

I do not wish to touch upon the legal effect; of course I have my own views. As there will be too many instances in the course of years will there be any necessity to validate all such documents registered offending the provisions of law or should the law be so interpreted to bring them all within the scope of the Registration Act.

Compensatory cost under Section 35A C.P.C. and appeals therefrom:

Under the C.P.C. a trial court when it orders compensatory costs as well to the successful party (it is the privilege of the trial court alone) usually the court never writes a separate order apart from judgment. Reasoning and conclusion forms part of the judgment and decree. The direction to pay compensatory costs too is incorporated as a clause in the decree.

But let us see Section 104(ff) C.P.C. which states that the order for payment of compen-

satory costs u/S.35A C.P.C. is an appealable order. So only a CMA u/S.104(ff) will lie (really there are two provisions relating to appeals against orders some under Order 43

Rule 1 and some under Section 104 C.P.C.

If so how can the direction to pay compensatory cost u/S.35A C.P.C. be made part of the judgment and decree. It evidently means/stipulates a separate order with reasoning to pay compensatory costs to be pronounced along with the judgment in the suit and without making it a part of the judgment and decree. Then a CMA can be filed against that order. The wordings in S.35A to the effect “after recording its reason…...make an order” also support this view. Further Section 2(a) C.P.C. also.

During my period of practice (I am just completing 70 years within a couple of months at the Bar and is still in active practice in civil Courts) even though occasions were very few. I have never come across a single instance (may be there are some who have followed the law) where separate order is passed regarding compensatory costs; in all such cases the same forms part of the judgment and decree alone.

If what is stated in the provisions of C.P.C. relating to this matter in the law, I feel that my view too is correct.

Trial of Civil cases – old and new procedures

When a civil case is taken up for trial in the courts in erstwhile Malabar District which was then part of Madras Presidency the procedure adopted was as contained in C.P.C. The counsel for the plaintiff will open the case and address the court briefly about the fact and the documentary evidence on his side in support of the reliefs prayed for. The moment he stops his submission, the query that comes from the Presiding Officer is “on what all points you want to adduce oral evidence not covered by the documents or by way of explanation regarding the recitals in the document etc., and have you witnesses too. After so getting the scope of oral evidence to be adduced by the party and witnesses if any from the counsel, the defendant will be called upon to open his case and the same query is repeated. The court having understood the scope of the suit, directs either party to lead evidence and the evidence of the parties follow continuously, usually without break, day to day. There was no piecemeal recording of evidence of parties and witnesses, which is the order of the day resorted to by lawyers generally. Further there will not be too many part heard cases at the same time as in the present day; examination will be brief, so also the cross examination, which will be confined to what is spoken to in chief. The court having understood the facts and disputes involved in the case can cut short or prevent unnecessary and irrelevant questions being put to the witnesses by either counsel.

After taking evidence, the court is fully equipped to deliver the judgment or reserve the same unless some questions of law are also involved. The argument that follow will also be short if not the court can draw the counsels attention to certain parts of evidence and make it short. The court can get clarifications too if necessary on certain matters during arguments. Then the matter is posted for judgment on a specified date. The judge who reserved his judgment after going through the papers feel that according to him there are other points not adverted to by both sides and which require clarification will repost the matter and get clarification to clear his doubts and then post the matter for judgment on a specified date. If the judgment is not ready on that date after giving written notice on acknowledgement of the counsel concerned, a further date will be notified for judgment. To save limitation, the date of judgment is important and that is why acknowledgment of the counsel is taken by serving notice on him.

If this method/procedure is followed as envisaged in C.P.C. how much time does an efficient intelligent presiding officer will take to dispose of a matter can very well be imagined. It will be a quick disposal of a case.

Now let us come to the present form of trial. When a matter is posted in the ready list and that case is taken up and the counsel either of the plaintiff or defendant as the case may be is called upon to put the party in the box. The party and witnesses are examined and cross examined by the counsel concerned. Such oral evidence is recorded by the court not knowing what the matter is about, what is the dispute etc., with the result he has no control over the examination in chief or cross examination as to whether the question put are relevant, necessary or irrelevant for considering the issue involved in the case except when the court has already gone through the pleadings earlier and understood the scope of oral evidence.

After 2002 amendment of the C.P.C. as the oral evidence is displaced by chief affidavit/proof affidavit, what we get at present in court in the form of chief affidavit is mostly nothing but a replica of the plaint or written statement as the case may be prepared by the counsel to which the party has subscribed his signature.

Regarding cross examination, mostly it is recorded by a commissioner, unless the court think fit to record evidence by itself.

If arguments too are avoided and written arguments take the place of oral submission, then what speaks from the stage of the plaint to the end are written and recorded notes in the form of a paper book as in an appellate court unlike living voice of the witnesses and the submissions of the counsel as in a trial court. Apart from oral submission written arguments too are necessary in the present day, as there is considerable delay in pronouncing judgments and hence at least to remind or recollect the facts or evidence, written arguments will be very useful for a presiding officer.

So in all, I am firmly of opinion that old is gold; the impression that the old method/pro-

cedure will consume more time etc., are futile expressions without the experience of a trial court work. One can very well imagine the difference in hearing a living voice (witness or counsel) and reading recorded evidence or written arguments.

So I suggest that for a proper trial of a civil case, counsel of either parties should open the case briefly detailing the matter in issue before evidence is recorded by the court itself and then hear the arguments on either side and pronounce judgment promptly. That will be the fair trial which will be appreciated by the legal fraternity and the litigant public and this process will consume less time if the matter is heard by an efficient presiding officer

I am reminded of what Justice H.R.Khanna said in his Book “Neither Roses nor thorn” about the most respected erudite learned lawyer Palkhiwala.

“The height of eloquee to which Palkhiwala rose on that day had seldom been equaled and never surpassed in the history of Supreme Court.

The Judges shine with reflected glory for their judgments, verily reflect the industry of the counsel appearing before them”.

(The reference is In reKeshavanand Bharati’scase).

A rich tribute to an outstanding lawyer.

That is the effect of submissions by a counsel before a presiding officer in any case.

Is Section 105 T.P. Act, definition section happily worded?

True as per the definition of lease both land and buildings which are immovable properties are taken in. But one will find reference regarding building only in two sub-clauses

in S.108, without using the word ‘Building’.

Section 108(f) speaks of “any repairs”, evidently meaning thereby a building and (j) which says “nothing in this clause shall be deemed to authorize” a tenant having an un-transferable right of occupancy” etc. But in this Act no where it is stated that a tenant will have only un-transferable right of occupancy as regards a building. Because of the use of the term tenant in this Act, in that sub-clause, one has to presume that it is with reference to a building. Is there any act which states that when a building is let out to a tenant, no estate of un-transferable occupancy is created. In all Sections under this Act except in S.108(j), there is no reference to a tenant, only lessee.

As I understand it, S.105 onwards relating to lease, takes in within its ambit tenants of buildings as well, who too are governed by the various provisions therein, but without transferable occupancy right. The same object or purpose would have resulted better if the definition of S.105 is properly worded with an exception relating to tenant of buildings so as to bring out the difference between the lessee of land and the tenant of a building.

In Kerala Act 2/65, a tenant is defined but such tenancy is made heritable and not alienable for the limited purpose of the various proceedings in a court of law, on the death of the original tenant, even though no “so called estate” is there to be inherited by his legal heirs which is marketable as in a leasehold of land.

Let me conclude by saying, I believe that I have given you the readers sufficient food for thought during this Covid 19 summer recess.

Any criticism or enlightment is welcome.

Are We Ready to Welcome Artificial Intelligence in Legal Services?

By Dr. P. Syamjith, Senior Executive in Legal Department of a Public sector Bank

04/07/2020

04/07/2020

Are We Ready to Welcome Artificial Intelligence in Legal Services?

(By Dr. P.Syamjith, Senior Executive in Legal Department of a Public-sector Bank *)

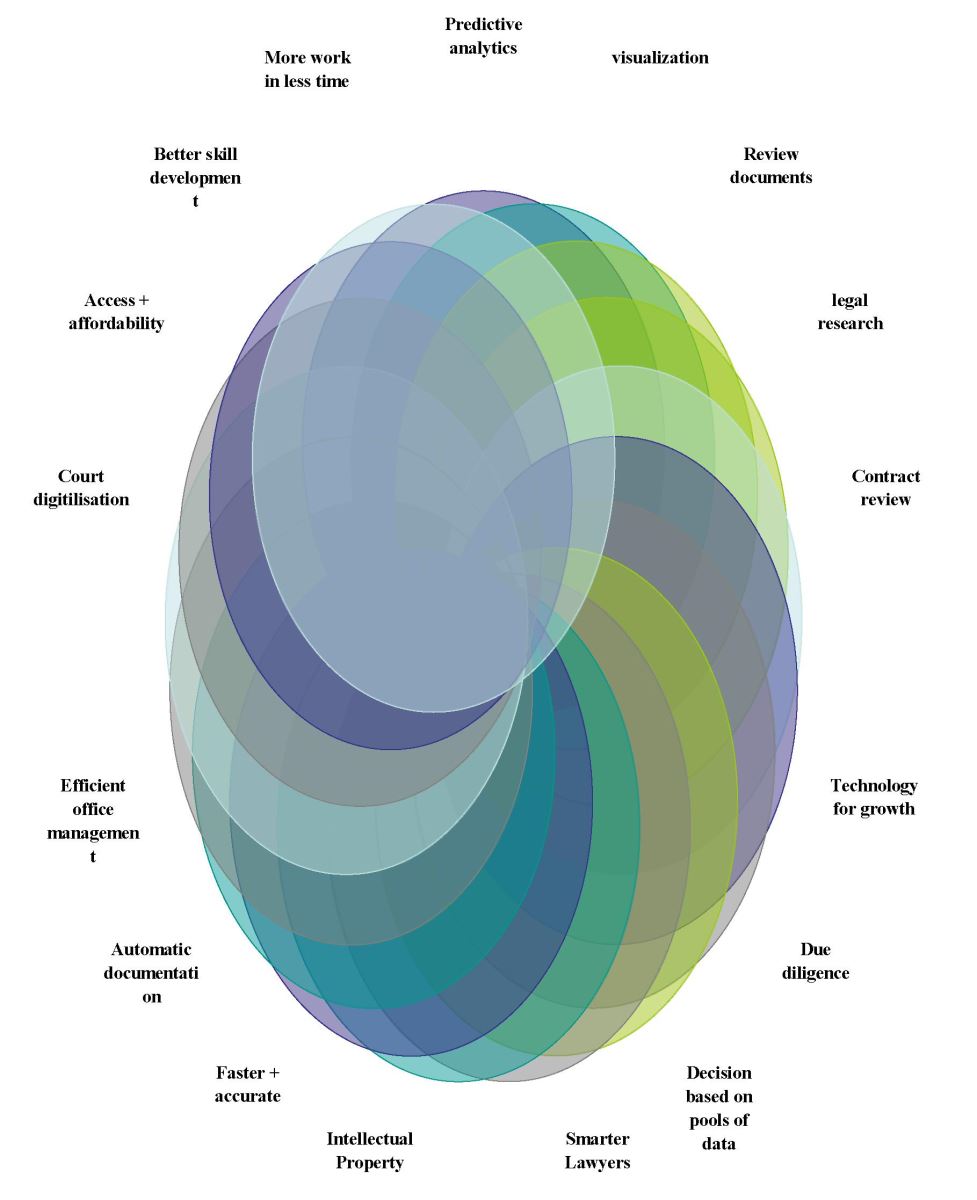

We are today living in a fast changing, uncertain but globally connected world and it is called as “VUCA World “i.e. - Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous world. In this “VUCA World”, Artificial intelligence (Al) is one innovation which has been drastically impacting the functional ecosystem of our society and affecting the way we live our lives.