Haelan Laboratories v. Topps Chewing Gum, 202 F2d 866

By Karni Singh Rajora & Krishnan Krishna K.

07/12/2009

07/12/2009

1. Hornstein v.Podwitz, 254 N.Y. 443, 173 N.E. 674, 84 A.L.R. 1.

2. Wood v.Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon, 222 N.Y. 88, 118 N.E. 214; Madison Square Garden Corp. v. Universal Pictures Co., 255 App.Div. 459, 465, 7 N.Y.S.2d 845;

3. Reiner v. North American Newspaper Alliance, 259 N.Y. 250, 181 N.E. 561, 83 A.L. R.23.

4 Carrie Rainen, "The Right of Publicity in the United States and the United Kingdom" (2005) 12 New Eng. J. Int’l & Comp. 197 at p.206.

5. N.S. Gopalakrishnan & T.G. Agitha, Principles of Intellectual Property, 1st edn., Eastern Book Company (2009).

6 David Tan, "Beyond Trade Mark Law: What the Right of Publicity can Learn from Cultural Studies", 25 Cardozo Arts & Ent. LJ. 913.

7. Winterland Concessions Co. v.Sileo, 528 FSupp 1201,1214, 213 USPQ 831 (ND III 1981).

8. Armand Cifelli and Walter McMurray, "The Right of Publicity: A Trade Mark Model for its Temporal Scope", 66 Journal of the Patent Office Society 455, 458 (1984).

9. Id at 470-71.

10. J.Thomas McCarthy, Trade Marks and Unfair Competition, 526(2d ed 1984).

11. Supp. 1277, 1282 (D. Minn. 1970).

12. Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets, Inc, 698 FD 831 (CA 6, 1983).

13. William L. Prosser, Handbook of the Law of Torts, § 117 (4th Ed 1971).

14. Supra n. 4.

15. 2003 (27) PTC 81.

A Decent Dissent on Domestic Violence

By Sreejith Cherote, Advocate, Kozhikkodde

30/11/2009

30/11/2009

1 Interpretation of Statutes - By Justice A.K.Yog. 1st Edition 2009.

2 . A.R.Auntlay v. R.S.Nayak (AIR 1988 SC 1531)

3 . M/s Furest Day Lawson Ltd v. Jindal Exports Ltd. (AIR 2001 SC 2293)

4 . Delhi Municipal Corporation v. Gurunam Kaur (AIR 1989 SC 38)

I Wish to be Reborn As a Lawyer Only

By T.P. Kelu Nambiar, Sr. Advocate, High Court, Ernakulam

30/11/2009

30/11/2009

N.I. Act S.138138 - Holder v. Drawer

By K.G. Joseph, Advocate, Aluva

23/11/2009

23/11/2009

MARRIAGE REGISTRATION - A progressive direction by the Supreme Court to protect the rights of married women

By Gaurav Kumar, Advocate, Supreme Court

17/11/2009

17/11/2009

MARRIAGE REGISTRATION

A progressive Direction by the Supreme Court to Protect the Rights of Married Women

Gaurav Kumar, Advocate, SC

“We cannot allow the dead hand of the past to stifle the growth of the living present. Law cannot stand still; it must change with the changing social concept and values. If the bark that protects the tree fails to grow and expand alongwith the tree, it will either choke the tree or if it is a living tree, it will shed that bark and grow a new living bark for itself. Similarly, if the law fails to respond to the needs of changing society, then either it will stifle the growth of the society and choke its progress or if the society is vigorous enough, it will cast way the law which stands in the way of its growth. Law must, therefore, constantly be on the move adapting itself to the fast changing society and not lag behind. It must shake off the inhibiting legacy of its colonial past and assume a dynamic role in the process of social transformation.” - Per P.N. Bhagwati, J., National Textile Workers Union etc. v. P.R. Ramakrishnan and Others, 1983 (46) FLR 38.

Marriages, as they say, are made in heaven and solemnised on earth. It is a sacrament (Sanskar) for Hindus, a sanctified contract for Muslims and sacrosanct knot for Christians. Husbands and wives vow for each other, yet there have been innumerable cases of betrayals by the spouses. In this context, the recent direction on Valentine Day, of the Supreme Court of India for compulsory registration of marriages is a welcome. Interestingly, this direction of the Apex Court has come during the course of hearing of a case of divorce petition. The maintenance suit was filed by one Seema against her husband Ashwini Kumar, who had disputed her marriage with him in the absence of any documentary proof which she had failed to produce.

.

.

The bench of Justice Arijit Pasayat and Justice S.H. Kapadia has now directed the governments to frame and suitably amend the rules to make the registration of marriages compulsory within three months and it would be applicable for all castes, communities and religious sects. The rules should be publicised and public should be given the opportunity to file objections if any within one month thereafter. The entire gamut of existing laws on marriage - for all communities -would remain intact and registration procedure and rules would be in addition to these. The National Commission for Women (NCW) has also been demanding for making the registration mandatory.

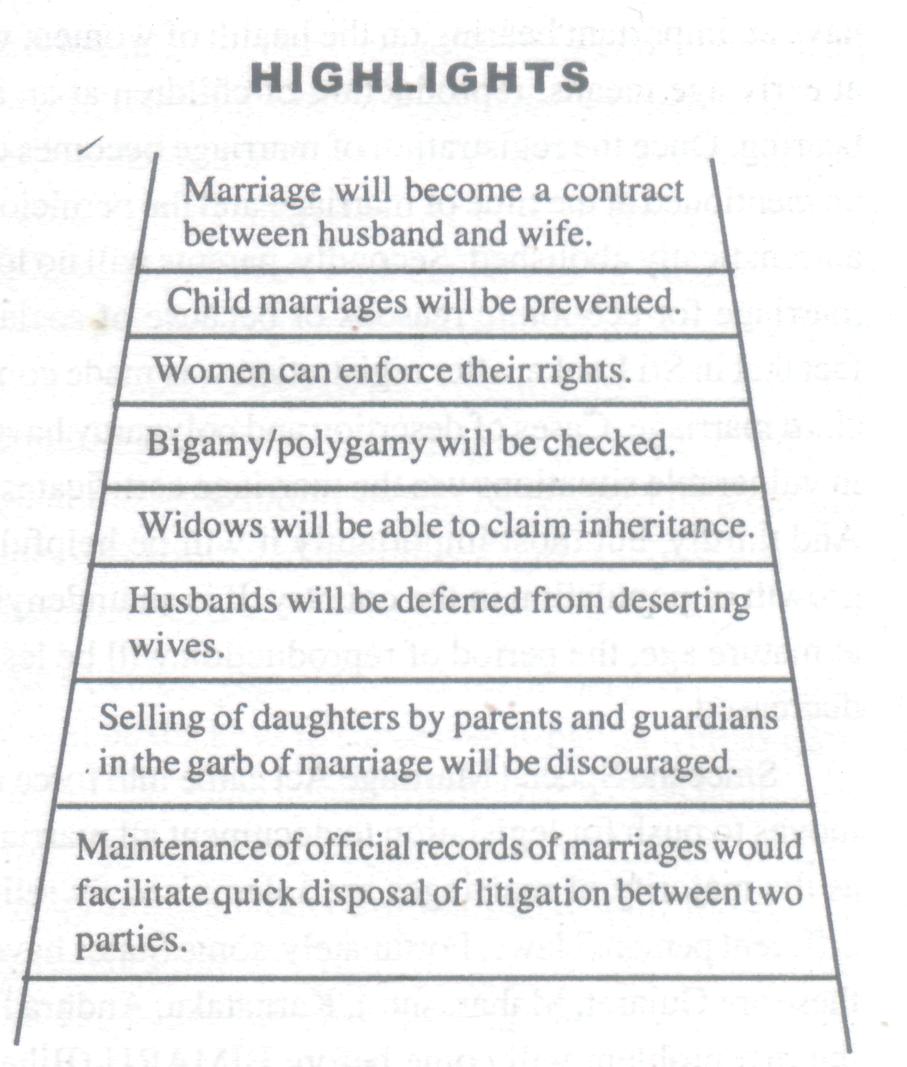

Needless to say, it is a breakthrough. It will aid the dismantling of the unhealthy social edifices of child marriage and the exploitation of married women. It is bound to have far-reaching benefits. Child marriage, although prohibited by Sharda Act in 1929, still continues in many communities. Every year on the occasion of Apha Teej thousands of child marriages take place only in Rajasthan. Compulsory registration will, undoubtedly, drastically curtail the child marriages ensuring the girl child the right to a free and wholesome childhood.

Marriage, and the institution of society predate modern society. The changing structure of family, from joint to nuclear, shows it is not independent of shifts in the economy, though the family is crucial for social reproduction of labour. Mandatory registration of marriage would compel society, at large, to recognise that. It will address the problems of women like bigamous husbands, property disputes or claiming maintenance following divorce. It will certainly empower women by upholding their rights in a country where more than 50 years after independence they are still treated as second class citizens and often left destitute on the death of their husbands or after divorce.

Now let us see in what way it will have salutary effect on the society. First of all, it will have an important bearing on the health of women, who get married at an early age. Marriage at early age means, reproduction of children at an age, when they are not capable of child-bearing. Once the registration of marriage becomes compulsory, the age of girl and boy has to be mentioned at the time of marriage and the pernicious practice of under-age marriage will get automatically abolished. Secondly, parents will no longer be able to sell their girl children into marriage for economic reasons or because of social compulsions. This is evidenced by the fact that in Sri Lanka, after registration was made compulsory, there was a dramatic decrease in child marriage. Cases of desertion and polygamy have significantly come down and the women in vulnerable situations use the marriage certificates in courts to assert their rights as spouses. And thirdly, but most importantly it will be helpful in curbing and controlling the alarming growth of population in the country. It is an undenying fact that once the women are married at mature age, the period of reproduction will be less and frequency of child-bearing will get decreased.

Since the Special Marriage Act came into force in 1954 for civil marriage, there have been moves to push for legislation to document all marriages. But these have fallen by the wayside as the majority of marriages are solemnised by religious rites and fall within the domain of different personal laws. Fortunately, some States have already taken lead in this regard. Among these are Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Himachal Pradesh. However, the real problem will come before BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) States, which have miserably failed so far to prevent child marriages.

S. 8 of the Hindu Marriage Act empowers the State Governments to make rules for the purpose of registration of marriages as there are various customary forms of marriage in different communities among the Hindus and it would be difficult to prove such customary forms. Under sub-s.(1) of S.8 of the Act, the parties to any marriage, may have the particulars of the marriage entered in the register. Though in sub-s.(2) prescribing the punishment, the words “any person” are used, where the State makes it compulsory to make entries in the register, both spouses will be liable for punishment if entries are not made. Even if the entries are made at the instance of one of the spouses only, the other spouse will not be liable for punishment. Sub-s.(4) provides the legislature intended to make the marriage register a public document within the meaning of S.74 of the Evidence Act and a certified copy of such public document can be produced in proof of the contents of the register. The same principle is adopted in this section. Sub-s.(5) states that the validity of any Hindu marriage shall, in no way, be affected by the omission to make the entry in the marriage register. It follows that the State Government is not empowered to make any rule invalidating a Hindu marriage on the ground of omission to make an entry in the marriage register.

The then State of Bombay, even prior to passing of the Hindu Marriage Act had passed the Bombay Registration of Marriages Act, 1953 for the registration of all marriages for all communities excepting civil marriages. For Parsi and Christian marriages, there are Central Acts providing for registration. After enactment of the said Act, the State of West Bengal in 1958, the State of Punjab in 1960, and the State of Andhra Pradesh in 1965 made rules in accordance with the S.8 of the Act.

As a matter of fact, it is going to be a boon in a country where marriages take place with little responsibility. There are instances of a man marrying one woman in one street and another in the next with impunity. What is, however, needed is that the procedure of registration should be made easy not complex and cumbersome as it exists today. At present for the sake of registration not only the husband and wife have to personally appear before the Registrar but they also have to produce two witnesses, who are the respectable persons of the society. The couples have to submit the affidavit, normally prepared by lawyers, photographs of marriage and invitation cards etc. as the proof of the marriage. This is dissuading without doubt. That is why the Supreme Court has made it clear that the registration should be made to be a facility not a penalty that too only twenty five rupees as stipulated by sub-s.(2) of S.8 of the Hindu Marriage Act which would reduce the justice to mockery.

The purpose of law can be best served when the registration is made very-very simple. Cost, access, and effective communication will be the keys to success in urban as well as rural areas. The cost of registration should be nominal. Easy and hassle-free access will be facilitated if, in towns and clusters of villages, post offices in addition to sub-registrar’s offices and, in villages, village administrative officers or gram pramukhs are entrusted with the job of registration. As in the case of compulsory registration of births and deaths, there must be a vigorous campaign to communicate the new rules of the game to all households, above all to women. It needs to be emphasised that, under extenuating circumstances, unregistered marriages should not stand invalidated. It has to be ensured that it needs little paper work. Although many specifies are yet to be settled, it is clear that the Supreme Court has struck a progressive blow for gender equality in India.