Are separation agreements between spouses valid

By J. Duncan M. Derrett, D. C. L., Professor of Oriental Laws in the University of London

20/06/2018

20/06/2018

Are separation agreements between spouses valid

(J. Duncan M. Derrett, London)

My article on “Are Separation Agreements between spouses valid” appeared unsatisfactory to Mr. P. R. Baldota who wrote a rejoinder entitled ‘‘Separation Agreements between Spouses” at 70 Bom. LR., Journal, pp.163-166.

In Mr. Baldota’s view there is a “fundamental distinction between the issue of the maintainability of a wife’s claim for maintenance under a separation agreement and the issue whether such an agreement can be a valid defence to a petition for restitution of conjugal rights.” He believes that agreements for separation are valid only for a time. He urges that the agreement is no longer binding after one party has tired of it and repudiated it; and that such agreements should not be a means whereby wives can buy freedom by making a down payment” (?), In his view as soon as a wife repudiates the agreement she can institute a petition for restitution, and the husband cannot plead that agreement as a defence.

Mr. Baldota quotes no authority for these views. In some respects they seem to run contrary to two well known principles, namely that agreements for consideration are not invalidated by unilateral repudiation by one party; and, more specifically in point, it is well known that ladies unlikely to remarry are keen to separate .from a spouse whom they can no longer bear, without having to undergo litigation and scandal and indeed the obloquy of being divorced. Separations by mutual consent are frequent in all classess of society, and it is usually only where further marriages are contemplated or family quarrels develop that litigation, and in particular litigation for divorce, breaks out. If it were to be possible for the spouse who has lived separate for some time to bring a restitution action wherever she chose, and so indirectly obtain a divorce although the husband is totally free from matrimonial offence against her, there would appear to be some irregularity in the law.

Yet, although I do not find myself convinced by Mr. Baldota’s arguments, he has raised, indirectly, a question of a much larger importance, de lege ferenda. England at any rate is moving towards a position in which breakdown of the marriageis the only or at any rate the principal ground for divorce. The heat of “matrimonial offences” will be taken out of divorce cases. No doubt, when the profession has adjusted itself, the result will be in many ways advantageous. I am not* so sure whether India is ready for such changes. It has not yet digested the changes of 1955. Yet there is something to be said constructively along the lines of conciliation, and in particular reconciliation. Courts are measuring up at last to their responsibilities. Procedure exacerbating trouble between husband and wife is beginning to be seen as against public policy. The Court must look into the real issues and not simply the pleadings (Chhote Lai v. Kamla Devi AIR. 1967 Pat. 269; M.Someswara v. Leelavathi AIR. 19.8 Mys. 274), and make a real endeavour to see to it (following the injunction written out in sec. 23 (2) of the Hindu Marriage Act) that the parties are reconciled.

If public policy requires that reconciliations are to be fostered two results seem to flow from this: (1) voluntary and equitable separation agreements should be encouraged rather than litigation; and (2) some means should be found whereby, when one party wishes to return, the aid of the court (so long as we do not have a lay matrimonial tribunal) should be sought to recall the other to the obligations of marriage and to discover the real impediments to the resumption of married life. It may be that restitution proceedings as at present envisaged are not the ideal way to achieve this, but it should be possible to devise a method whereby when the recalcitrant party pleads the separation agreement the petitioner should be entitled to show that there has been a material alteration in the facts such as would undermine the permanent validity of the agreement, thus allowing the other party to be in desertion.

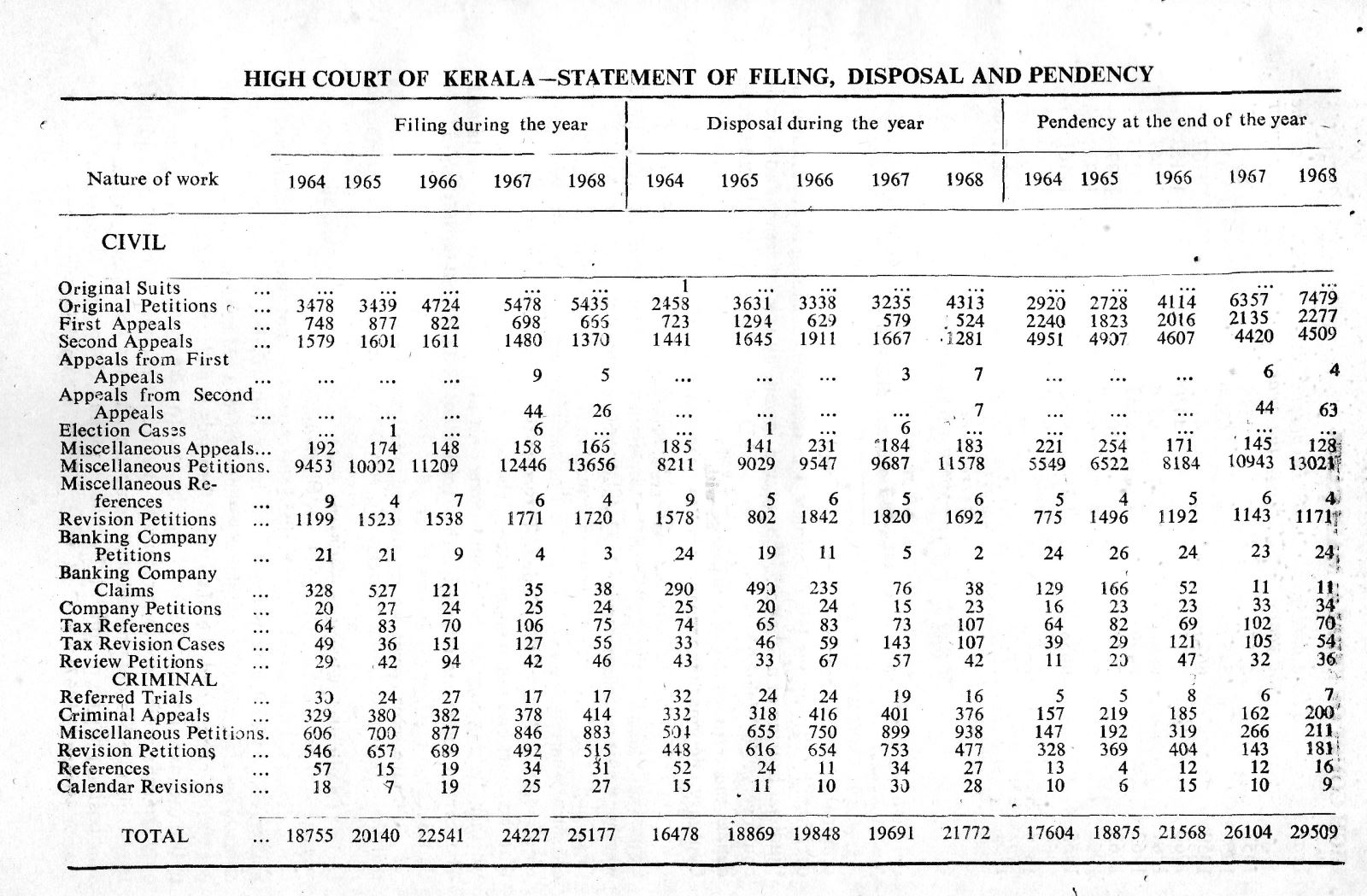

High Court of Kerala Statement of Filing, Disposal and Pendency

By A Well-Wisher

20/06/2018

20/06/2018

High Court of Kerala Statement of Filing, Disposal and Pendency

HIGH COURT OF KERALA MAIN CASES

|

Year

|

Filing during the year

|

disposal during the year

|

Pendency at the end of the year

|

| 1957 | 4167 | 3596 | 5580 |

| 1958 | 5450 | 4394 | 6636 |

| 1959 | 6673 | 4142 | 9167 |

| 1960 | 6915 | 4930 | 11152 |

| 1961 | 10099 | 6804 | 14447 |

| 1962 | 8499 | 9733 | 13213 |

| 1963 | 7864 | 10102 | 10975 |

| 1964 | 8696 | 7763 | 11908 |

| 1965 | 9438 | 9185 | 12161 |

| 1966 | 10455 | 9551 | 13065 |

| 1967 | 10935 | 9105 | 14895 |

| 1968 | 10638 | 9256 | 16277 |

Is it sufficient to implead the Receiver alone in an application u/S. 31 of the Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1964

By M.N. Ganapathy Iyer, Advocate, Palakkad

18/06/2018

18/06/2018

Is it sufficient to implead the Receiver alone in an application

under S. 31 of the Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1964

(M.N. Ganapathy Iyer, Advocate, Palghat)

S. 31 (2) of the KLR. Act enjoins that “on receipt of an application under sub-section (1) the Land Tribunal shall issue notices to all persons interested, and after inquiry determine” etc. The requirement as to impleading all persons interested is based on the principle that a person whose interest is not represented in an adjudication cannot be bound by it.

2. It has been held by the Kerala High Court in 1960 KLT. 68 (73) that the Receiver appointed by a Court is only a caretaker and he has no interest in a legal sense, in the estate under his charge.

3. Even assuming that the Receiver has any interest in the estate, the requirement under S. 31 (2) is that all persons interested’ have to be impleaded.

The parties to the suit have thus to be impleaded, so that the adjudication can affect and bind their interests.

4. S. 104 of the same Act, however, provides in Sub-S. (1) “Where in any proceeding under this Act etc.” and then in sub-section (2) “Where any such proceeding relates to any property or part thereof under the management of a Receiver appointed by a Court, it shall be sufficient to implead the Receiver as party to the proceeding”.

5. S. 104 of the KLR. Act is thus seen to be a general provision applicable “to any proceeding under this Act”, directed, inter alia, against an estate managed by a Receiver. S. 31, however, is a section specifically providing for an application for determination of Fair Rent.

6. An application for determination of Fair Rent is one affecting radically the interest of the parties concerned, by altering the quantum of rent which’ reflects the value of such interest. All applications, however, do not affect such interest to the same extent. For instance, an application under S. 26 for recovery of arrears of rent payable by the estate; and again, an application under S. 46 (2) accompanying a deposit of rent due to the estate. In such applications, the impleadment of the Receiver appears to be sufficient, because they have only a bearing on the caretaking aspect which sits squarely on the shoulders of the Receiver.

7. There is thus a conflict between S. 31 (relating to determination of Fair Rent) which enjoins that all persons interested shall be impleaded and S.104 which provides that “in any proceeding under this Act” relating inter alia to an estate managed by a Receiver, it shall be sufficient to implead the Receiver. In such cases, where there is a conflict or incompatibility between two provisions in the same enactment, the rule of construction to be followed is to reconcile” the two by treating the specific provision as an exception to the general provision and implementing the specific provision (AIR. 1928 Lahore 609 FB.)

8. There is also the further question whether a Receiver who is a creature of common law and Central statute (Act V of 1908) and who, as held in 1960 KIT. 68 is a mere caretaker, can be clothed with interest in property by a State enactment. Unless the Receiver is considered as being so clothed with such interest, the Receiver cannot commit the interests of the various parties to the adjudication. Hence, the relevant provision in S. 104 must be regarded as unavailing for this purpose, in a Constitutional sense.

9. For the above reasons, it appears to be fairly obvious, that for an adjudication of Fair Rent under S. 31 of the KLR. Act to be binding on the estate managed by a Receiver, and on the parties to the action, all the parties interested should be impleaded, besides the Receiver himself, who can only be a technical or proforma party.

Take Coginizance of

By P.S. John, Advocate, Kottayam

18/06/2018

18/06/2018

TAKE COGNIZANCE OF

(P.S. John, Advocate, Kottayam)

The expression “take cognizance of” is not defined in the Code, civil or criminal, and the absence of a precise definition seems to have led to conflicting decisions by the various High Courts. The dictionary meaning of cognizance is, “judicial hearing of a matter; the power given by law to hear and decide controversies” (Webster’s New International Dictionary). Wharton’s Law Lexicon defines the term as “the hearing of a thing judicially” and according to the Centuary Dictionary the meaning is “to hear and determine”.

In 1955 KLT 553 Justice T.K. Joseph has sought to distinguish the expression “take cognizance” from “entertainment”. There the question arose whether a suit regarding service Inam land which under S. 8 of the Travancore CPC. had to be filed with government sanction could be taken cognizance of, without such sanction. The plaint was not accompanied by government sanction as required by S. 7 (a) of the Code. The question arose whether it could be said that the court had taken cognizance of the suit the moment it was instituted or whether ‘taking cognizance” would come only after the sanction was obtained. The learned Judge has referred to the decision in 28 TLR. 250 on this point. In that decision the learned Judges observed:

On the second point, we are disposed to follow the ruling in 8 Cal. 422 and hold! that the original defect did not prevent the suit from proceeding, after the government sanction required under S.7 of the CPC. was received. See also 17 Bom. 169 where it was held that a suit filed without a certificate could not be treated as bad ab initio. To ‘cognize’ is to hear and determine and not simply to entertain”.

So, until the sanction is obtained the court does not take cognizance of the matter. The plaint filed without sanction is nevertheless entertained by the court. So also, where a complaint is filed before a Magistrate in respect of a cognizable offence and the Magistrate forwards it under S. 156 (3) Cr. PC. to the police for investigation, the court may be said to take cognizance of the offence, only after the police report is received. Until that is done, it could be said that the Magistrate has entertained the complaint but has not taken cognizance of. This position has been upheld by the Supreme Court in Abhinandan Jha v. Dinesh Mishra ( (1967) 3 S. C R. 668). There, a complaint regarding a cognizable offence was forwarded by the Magistrate to the police for report. The learned Judes observed:-

“If the report is a charge sheet under S.170 it is open to the Magistrate to agree with it, and take cognizance of the offence under S.190(1)(b); or to take the view that the facts disclosed do not make out an offence and decline to take cognizance.”

So, taking cognizance or hearing of the thing judicially takes place only after the police report is received Before that it could be said that the complaint had been entertained; but not taken cognizance of.

A Division Bench of the Allahabad High Court in Badri Prasad Gupta v. Kripa Shankar (AIR 1967 All. 468) has further clarified this position using a figurative expression which is interesting reading. According to them as soon as a complaint is filed the case is ‘conceived’ and the case so conceived remains in the womb till the police report is received and it is brought forth either alive or still-born after the receipt of the police report. Just as in the Supreme Court decision quoted above, if the Magistrate agrees with the police report he can take cognizance of the offence; if he disagrees he can decline to take cognizance. So, from the mere fact that the Magistrate has entertained a complaint it cannot be said that he has taken cognizance of it. It is open to the Magistrate to postpone taking cognizance to a later date, i. e., after the police report is received.

Basing on the above Division Bench ruling of the Allahabad High Court, a Single Bench of the Kerala High court in 1968 KLT 57 has held that the Magistrate can be said to have taken cognizance, in a proceeding under S.156(3) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, only after the Police report is received. This decision as well as the decision of the Allahabad High court (cited supra) have been severely criticised and dissented from by a later Single Bench of this court in Madhavan Nair v. Gopala Panicker(1968 KLT. 547) following an earlier decision of the Supreme Court, Jamuna Singh v. Bhadai Shah(ATR 1964 SC 1541). But that decision of the Supreme Court does not take us anywhere. That decision only says that a case can be said to be instituted in a court only when the court takes cognizance of the offence alleged therein. This is simply begging the question. When does a court take cognizance of an offence? Is it when a complaint is filed or only when the Magistrate passes a judicial order on a complaint after the police report is received? In deciding this point the 1964 Supreme Court case cited supra, does not help us. A Magistrate can be said to take cognizance of an offence in the case of a private complaint, only when he hears the thing judicially and passes a judicial order; and when the complaint is forwarded to the police this can happen only after the police report is received. He applies his judicial mind and takes cognizance of the matter, only after the police report is received. As observed in 1968 KLT 57:

“When a complaint is sent by the Magistrate to the police it must be presumed that such a step was resorted to by the Magistrate for a further assurance about the truth of the complaint. Putting it differently, the Magistrate is not prepared to proceed on the complaint alone; but thinks it necessary that a police report also should be obtained.”

To me it appears on the strength of the authorities quoted above, that the Magistrate can be said to take cognizance of the offence complained of, only when he passes a judicial order on the complaint and proceeds to “hear and determine” and not when he gives an executive direction to the police for investigation and report. The decision reported in 1967-3 SCR 668 is a clear exposition of the law on this point and the Division Bench of the Allahabad High Court has only given expression to the same principles though in a figurative language. 1968 KLT 57, in the circumstances, must be held to have laid down the correct law.

Task Of Attorney-General

By Rt. Hon. Sir Elwyn Jones, Britian’s Attorney General

18/06/2018

18/06/2018

TASK OF ATTORNEY-GENERAL

(From the address of Britian’s Attorney General, Rt. Hon. Sir Elwyn Jones

in Indian Law Institute at New Delhi on 13.1.69)

I do not know how you fare as Attorney-General, but I assure you that the Attorney-General of the United Kingdom has not always been greatly loved. Francis Bacon, my great predecessor came - as you will remember - to a rather sticky end when he was Lord Chancellor because he accepted bribes from both sides: bad thing for any judge to do; bad enough to accept from one, worse still to -accept from two. And he described the task of Attorney-General as the painfullest task in the realm. A more recent Attorney, Sir Patrick Hastings, said that to be an Attorney-General was to be in hell. I do not entirely agree with that; for instance, it has brought me to India.

And the great commentator on the law and its practices, Matthew, was once asked to state what is the difference between Attorney-General and Solicitor-General. And he said broadly speaking it is the difference between the crocodile and the alligator. That is our reputation, and I hope that you fare better in your standing.

x x x x

And I fear that our institutions owe more to historical development than to any principles of constitutional tidiness. Their only virtue, if I may say so, is that they seem to have passed the critical test-they work. But it is a picture of some confusion. The Lord Chancellor, for instance, defies all the laws of separation of powers. He is a member of the Cabinet, and therefore at the heart of the executive. Ha is a Speaker of the House of Lords and therefore an important part of the legislature. And, finally, he is head of the judiciary, and what more terrible animal could there be than the head of the judiciary who is also in the heart of the executive and a legislator at the same time.

I myself as Attorney also wear a number of hats and T sometimes feel lam a kind of universal joint in the machinery of government-sometimes feel out of joint, I fear, too from time to time. I am a Minister of the Crown and a Member of Parliament but when 1 perform duties like deciding whether to prosecute in a given case or not or to enter a nolle prosequi, I of course act in a quasi-judicial capacity and must have no regard to party political considerations at all. And heaven knows the Attorneys in my country had a very stern warning in this field in the first Labour Government which was brought down because it’was alleged that Sir Patrick Hastings, having decided to prosecute Mr. Campbell, the editor of the Workers’ Voice, was, it was said, told by the Cabinet not to do so. The prosecution was withdrawn and in the ensuing protest about this alleged interference by the executive with the administration of justice the Labour Government fell. Well, I would not like to have that responsibility on my shoulders. We are in enough difficulty as it is x x x.