Artificial Intelligence and Law

By V. Gokul Pillai, 4th Year EEE Student, Amrita University, Amruthapuri, Kollam

06/01/2021

06/01/2021

Artificial Intelligence and Law

(By V. Gokul Pillai, 4th Year EEE Student, Amrita University, Amruthapuri, Kollam)

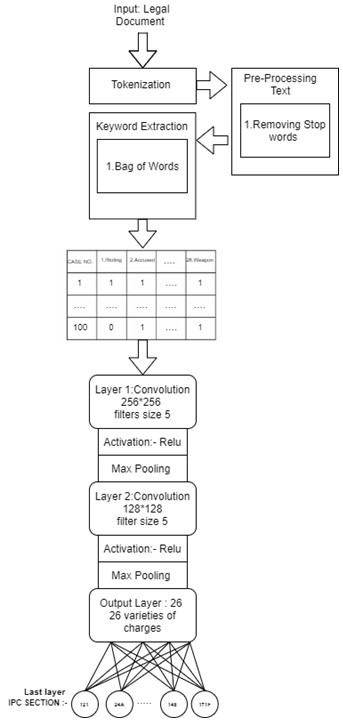

The approach of this study was to highlight the importance of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) in the legal domain. The proposed technique was of Bag of Words technique i.e., one of the NLP tool to analyze the text of the court proceedings to extract the keywords from the text and CNN to classify each case into its charges (as per judicial law of India), to predict whether it is a bailable or a non-bailable offence and to give an approximate judicial decision. The results showed that this method has an average accuracy of 85% in prediction based on the IPC (Indian Penal Code) which is extracted from the case files, judicial pronouncements and the constitution of India.

Gokul Pillai explains that from the perspective of a developer, Legal data is heavy and generally the requisite information is bundled with irrelevant information. Under such circumstances, the use of a natural language processing toolbox to obtain required data (keywords) is indispensable. The bag of words models used in the experiment will learn vocabulary from all the documents and then models each document by counting the number of times each word appears. By using this Bag of Words algorithm, the required keywords can be obtained from the document at ease, opines Gokul Pillai. In this model, a text is represented as the bag of its words, ignoring grammar and arrangement of the words but keeping multiplicity. The Bag of Words methods are used when the frequency of each word in the context is to be ascertained, and by such the keywords in a case can be identified. It is those keywords so ascertained that will be the features of that case. The next technique in this artificial intelligence model propounded by the authors in this work is called Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) used for the classification purpose. Since the convolutional neural network were originally designed to perform deep learning task, it uses the concept of a “convolution”, a sliding window or “filter” that passes over the array of input, identifying important features and analyzing them one at a time thereby reducing them down to their essential characteristics and repeating the process until the final product is made out.

In this paper the last layer of CNN represents 26 varieties of charges which are taken from the constitution of India. After identifying the charges, the proposed model will be able to separate it as bailable or non-bailable cases. And for each charge, there is a separate verdict that can be mapped to it. Verdict for violation of more than one charge is given by mixing the verdicts of those two charges. Gokul Pillai suggests that this model can be exported and used for making websites so that even a common man with limited legal knowledge can get a brief idea of the judgement before approaching the court. As of now artificial intelligence is not capable of making fool proof decisions, but the authors suggest that the future beholds a scenario where AI will be capable of making unbiased and well-analyzed decisions.

Humans, Please be Kind to Animals

By Dr. Kauser Edappagath, District & Sessions Judge

06/01/2021

06/01/2021

Humans, Please be Kind to Animals

(By Dr. Kauser Edappagath 1)

“The greatness of a nation and its progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated”. -- Mahatma Gandhi

Recently, in a gruesome act, a pet dog was tied to the boot of a car and dragged along a road by a man to be abandoned in the wild, but freed after a passerby confronted him in Ernakulam district, Kerala. Not quite long ago, a pregnant elephant in Kerala’s Silent Valley Forest fell victim to an act of human cruelty after a pineapple filled with powerful crackers offered by a man exploded in her mouth when she chomped on it. The 15-year-old elephant walked for days in pain before dying, standing in a river. The incident near Chennai, in 2016, where two final-year medical students threw a puppy off a tall building and filmed the incident, must count as the height of cruelty that one has come across.2

Animal neglect and violence has now become common practice across the globe. Physical violence, emotional abuse and life-threatening neglect are daily realities for many animals. Cruelty and neglect cross all social and economic boundaries and media reports suggest that animal abuse is common in both rural and urban areas. The shocking number of animal cruelty cases reported every day is just the tip of the iceberg—most cases are never reported. Unlike violent crimes against people, cases of animal abuse are not officially compiled by state, making it difficult to calculate just how common they are.For a country that claims adherence to ahimsa, India’s treatment of its animals betrays a moral failure. Over the past year alone, there have been reports of animals being subjected to sexual abuse, acid attacks, being thrown off rooftops, and being burnt alive.3

Intentional cruelty to animals is strongly correlated with other crimes, including violence against humans. People who abuse animals are cowardly – they take their issues out on the most defenceless victims available – and their cruelty often crosses species lines. Research in psychology and criminology shows that animal abusers tend to repeat their crimes as well as commit similar offenses against members of their own species. A study conducted by Northeastern University and the Massachusetts SPCA in the US found that people who abuse animals are five times more likely to commit violent crimes against humans. Behavioural profiles of criminals by the FBI have consistently shown that many serial murderers and rapists had abused animals in their childhoods.4A survey of psychiatric patients who had repeatedly tortured dogs and cats found that all of them had high levels of aggression toward people as well.5

Overview of Animal Protection Laws

Protection of animals is enshrined as a fundamental duty in the Indian Constitution and there exist several animal welfare legislations in India such as the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 and the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 at the Central level and cattle protection and cow slaughter prohibition legislations at the State levels. The Constitution of India makes it the “duty of every citizen of India to protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife, and to have compassion for all living creatures.”(Article 51-A (g)). This Constitutional duty of animal protection is supplemented by the Directive Principle of State Policy under Article 48A that “the State shall endeavor to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country.” Both the above constitutional provisions were introduced by the 42nd Amendment in 1976. Killing, maiming, poisoning or rendering useless of any animal is punishable by imprisonment for up to two years or with fine or with both, under Section 428 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Under Section 429 of the Code, the term is 5 years and is applicable when the cost of the animal is above 50 Rs.

The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 is the first legislation made in post-independence India for welfare of animals. The objective of the Act is to prevent the infliction of unnecessary pain or suffering on animals and to amend the laws relating to the prevention of cruelty to animals. Under the Act treating animals cruelly is punishable with a fine of Rs. 10 which may extend to `50 on first conviction. On subsequent conviction within three years of a previous offence, it is punishable with a fine of `25 which may extend to `100 or imprisonment of three months or with both. Performing operations like Phooka or any other operations to improve lactation which is injurious to the health of the animal is punishable with a fine of `1000 or imprisonment up to 2 years or both. In 2017 new four Rules were enacted under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 to regulate dog breeders, animal markets, and aquarium and “pet” fish shop owners. The rules are the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Dog Breeding and Marketing) Rules, 2017; the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Regulation of Livestock Markets) Rules, 2017; the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Aquarium and Fish Tank Animals Shop) Rules, 2017; and the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Care and Maintenance of Case Property Animals) Rules, 2017. According to these new Rules, dog breeders, aquarium and fish “pet” shop owners must register themselves with the state Animal welfare Board of the respective states. No aquarium can keep, house or display any cetaceans, penguins, otters, manatees, sea turtles and marine turtles, artificially coloured fish, any species of fish tank animals listed in the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, or any species listed under the Appendix I of the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species. The sale of all types of cattle, including buffaloes, and camels for slaughter via animal markets is not allowed. The sale of cattle and camels can be made only to a person who carries valid documents proving he or she is an “agriculturist”. Certain various cruelties that commonly take place at markets including hot branding and cold branding, mutilating animals’ ears, force-feeding animals fluid to make them appear fatter to fetch a better price and more are also not allowed. No animal can be used for the purpose of entertainment except without registering under the Performing Animal Rules,1973. Dissecting and experimenting on animals in schools and colleges is bannedin India, under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act.

Through the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules (Second Amendment), 2014, animal testing for cosmetic products was prohibited all over India. Any person who violates the Act is liable for punishment for a term which may extend from 3 to 10 years or shall be liable to a fine which could be `500 to `10,000, or both. According to Rule 135B of the Drugs and Cosmetic (Fifth Amendment) Rules, 2014, no cosmetic that has been tested on animals shall be imported into the country. According to Animal Birth Control Rules, 2001, dogs can be sterilized only when they have attained the age of at least four months and not before that. Keeping, or confining any animal chained for long hours with a heavy chain or chord amounts to cruelty on the animal and punishable by a fine or imprisonment of up to 3 months or both. According to section 98 of the Transport of Animals Rules, 1978, animals should be healthy and in good condition while transporting them. Any animal that is diseased, fatigued or unfit for transport should not be transported. Furthermore, pregnant and very young animals should be transported separately.

As compared to these laws, the Wildlife Protection Act,1972 is a better equipped legislation along with appropriate fines and imprisonments and at the same time has a requisite framework to carry out its enshrined purpose.. The Act prohibits the killing, poaching, trapping, poisoning, or harming in any other way, of any wild animal or bird. According to Section 2(37) of the act, wildlife includes any animal, aquatic or land vegetation which forms part of any habitat, thus making the definition a wide and inclusive one. Section 9 of the Act prohibits the hunting of any wild animal (animals specified in Schedule 1, 2, 3 and 4) and punishes the offense with imprisonment for a term which may extend to3 years or with fine which may extend to `25,000/- or with both. The Act allows the Central and State Government to declare any area ‘restricted’ as a wildlife sanctuary, national park etc. Carrying out any industrial activity in these areas is prohibited under the Act. Section 48A of the Act prohibits transportation of any wild animal, bird or plants except with the permission of the Chief Wildlife Warden or any other official authorised by the State Government. Section 49 prohibits the purchase without license of wild animals from dealers. Section 16 (c) of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 also makes it unlawful to injure, destroy wild birds or reptiles, damaging their eggs or disturbing their eggs or nests. The person found guilty can be punished with an imprisonment of 3 to 7 years and a fine of Rs. 25,000. Teasing, molesting, injuring, feeding or causing disturbance to any animal by noise or otherwise is prohibited according to the section 38(j) of the Act. Anyone found guilty of this offence may face an imprisonment of up to 3 years or a fine of up to `25,000 or both. The Wildlife Protection Act is applicable to aquatic animals too. Protection of marine species in India is done through creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPA). Birds, too, are protected under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and in Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960, alongwith land and aquatic animals. Laws relating to zoo animals are also found in The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.

Although a lot of elaborate and specific animal protection laws as mentioned above have been in force in India, they are not sufficiently strong or strict enough to truly deter crimes against animals. The penalties prescribed under the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 for cruelty against animals are meagre ranging from `10- 500 where offences have been committed in violation of Sections 11, 20 or 26. The law is not strictly enforced and contains several provisions which provide leeway through which liability can be escaped. An additional leeway provided by the Act is that under Section 28, nothing contained in the Act shall render it an offence to kill any animal in a manner required by the religion of any community. Considering the diversity of religions and traditions in India, this Section was considered imperative. The general anti-cruelty parts in Section 11 of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 can be made a lot more effective by increasing the punishment and fine to some extent. The laws under the sections 428 and 429 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 do no justice to the animal lives and prescribe meagre fines for killing and maiming of such animals. The provisions for animal protection in the Indian Constitution remain principles instead of concrete law enforceable in courts.

Role of Judiciary in protecting Rights of Animals

Eventhough various animal protection laws in force in the country are inept, over the years Indian courts have developed a growing legal jurisprudence in animal law. The apex court has spent precious judicial hours contemplating how to induce humans to treat animals with compassion. In Animal Welfare Board of India v. A. Nagaraja6 (popularly known as “Jallikkattu Case”) the Supreme Court historically extended the fundamental right to life to animals. It held that bulls have the fundamental right under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution to live in a healthy and clean atmosphere, not to be beaten, kicked, bitten, tortured, plied with alcohol by humans or made to stand in narrow enclosures amidst bellows and jeers from crowds. The Supreme Court declared that animals have a right to protect their life and dignity from human excesses. Article 21, till then, had been confined to only human life and dignity. In another case dealing with the rights of captive elephants used in Kerala for temple festivals like Thrissur Pooram, the Supreme Court put temple managements and private owners of the elephants on a tight leash, cautioning them with criminal prosecution and “severe consequences” if they were found torturing the animals merely for the sake of the grandeur of the festival. In December 2015, in another case, the Supreme Court asked the Central government to clarify whether it was cruelty to employ elephants for joyrides. A month prior to that, in November 2015, the court had also asked the government to respond on whether exotic pet birds were safer in cages or do they have a fundamental right to fly. This debate was between the right to livelihood of pet shop owners and the right of birds to live freely. Animal lovers want the apex court to ban practices like ringing, tagging and stamping of birds.7

In April, during the initial stages of the lockdown, the Kerala High Court directed the district administration to issue vehicle pass to the owner of cats to ensure that his cats got their favourite biscuits, opening its doors to legal redress for four-legged beings. The court traced the right of the petitioner and, incidentally, of his cats to Article 21 — a facet of the citizen’s right to life, liberty and privacy. It also relied upon the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in the 2014 Jallikattu case which declared that an animal’s right to humane treatment was part of “life”, defined expansively to include the lives of animals.

The court bolstered its conclusion by invoking Article 51-A[g] — a fundamental duty that obliges citizens to show compassion towards living creatures. Recently Punjab and Haryana High Court has held animals to be legal persons. This is a welcome step in the Indian jurisprudence. While delivering the judgment Justice Rajiv Sharma, in his order said, “All the animals have honour and dignity. Every species[s] has an inherent right to live and is required to be protected by law. The rights and privacy of animals are to be respected and protected from unlawful attacks.”8

The animal protection laws in the country should be made more stringent and all-encompassing in order to address the ever growing animal abuse and to ensure animal welfare. In developed countries adjudicating custody arrangements for pets can be as intense as custody battles for children in matrimonial disputes. Pet custody legislations in the US embrace the concept of a ‘companion animal’. Though the primary basis of this arrangement is treating pets as property, the courts have evolved human-like standards in awarding custody reckoning the preferences of pets, ordering “petimony”, visitation rights, etc. In the West pet rights have even been tested, albeit negatively, in inheritance laws. Many American state legislations, however, provide for establishing a trust to care for pets named in the owner’s will.9There is a still a long ways to go in truly developing a solid foundation for animal law in India.

However, mere enactment of stringent laws is not sufficient. What we need today is widespread acceptance of animal protection as a serious social issue. Indian society essentially treats animals as non – sentient objects, and yet they aren’t. They suffer just as we do. Notably, as of November 2019, 32 countries formally recognize non-human animal-sentience, they are: Austria, Australia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Chile, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. It has been proposed that the United Nations pass the first resolution recognizing animal rights, the Universal Declaration on Animal Welfare, which acknowledges the importance of the sentience of animals and human responsibilities towards them. Civil society in India should come forward to adopt animals as social companions.

Earth was evolved for all life, not just for human life. Animals should be respected as citizens of the earth. Animal rights should be defined beyond mere existence. It takes nothing from a human to be kind to animals.

Foot Notes:

1. The Author serves as District & Sessions Judge in the Kerala Higher Judicial Service.

2. “Medicos in the dock for throwing puppy off building”, The Hindu, Chennai Edition, 6 July 2016.

3. Maniktala, Parth, “For the welfare of animals”, The Hindu, 18 September 2020.

4. “Animals are not ours”,http://www.peta.org.uk/issues/animals-not-abuse/cruelty-to-animals (Last accessed on 18 December 2020).

5. Lan R, Felthous, M.D., “Aggression Against Cats, Dogs, and People,” Child Psychology and Human Development 10 (1980): 169-77.

6. 2014 (2) KLT 717 (SC) = 2014 (7) SCC 547.

7. Rajagopal, Krishnadas, “Jallikkattu verdict spurred a flood of animal rights cases in Supreme Court”, The Hindu, 22 January 2017.

8. R.Nath, Naveen, “Do animals have a legal persona?”, Buisiness Line, 8 Octobar 2020.

9. Supra

Can Carpenter Carve Out New Canons of Evidence

By Sreejith Cherote, Advocate, Kozhikkodde

01/01/2021

01/01/2021

Can Carpenter Carve Out New Canons of Evidence

(By Sreejith Cherote, Advocate, Kozhikode)

1. The law and technology is on a perpetual race, where the law is always chasing technology to be at par with it, so that the society is not affected by the distance. In this race there are always checkpoints where only technology is required to endure an acid test to confirm its competency to survive the essential principles of law. Any new law or a rule of evidence introduced to keep pace with technological development has often been called upon to endorse their allegiance to the rule of fundamental justice. However apt, update and advantageous the novel rule is, it can never be permitted to govern society unless hallmarked by constitutionality. It may sometimes embarrass a layman, the attitude of Apex Court in discarding significant investigative advantage of law enforcing agencies for the sake of historically valued legal concepts and for the sake of constitutional validity. Nevertheless such principles are the eternal safeguards of inviolable human rights.

2. A decision of United States Supreme Court in Timothy Ivory Carpenter, Petitioner v. United States1is an example wherein the Supreme Court of United States has discarded the technological evidence collected by the investigation agency as violative of the constitutional rights guaranteed to an American citizen by the Fourth Amendment of the American Constitution. The decision even though pronounced in United States has got some vital aspects of law and technology which can be applied for the Indian legal system as well, concerning the use of cell phone data in proving crimes. The decision assumes importance here for the reason that, in India the investigating agencies are heavily relying on historic cell phone data obtained by third party service providers for the purpose of prosecuting offenders completely disregarding the right of privacy which Supreme Court of India in Puttaswamy & Anr. v. Union of India 2had held to be an integral part and inbuilt in Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

3. To understand the whole scenario properly we should begin by learning some provisions of American Constitution and other law and rules in force in United States of America along with the brief facts of the case. The 4th Amendment3 of the American Constitution read that “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to.

4. Stored Communication Act 4(hereinafter referred in sort as SCA) enables the US Government to compel third parties including mobile companies to produce historical data records electronically stored communication from third parties if such information is “specific and attributable facts showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe” that records at issue “are relevant and material to an on-going criminal investigation even without a warrant.

5. Third-party Doctrine

United States v. Miller 5– In this case decided by the United States Supreme Court in the year 1976 the court held that documents of an individual voluntarily given to a third party is not entitled for any protection under the FOURTH AMENDEMENT of the Constitution and a person cannot claim legitimate expectation of privacy with regards to information voluntarily given to third parties.(For example personal information given to banks). Same position was elaborated and confirmed by the Supreme Court of United States in Smith v. Maryland 6(1979) enabling the Government to obtain information without a warrant, data’s voluntarily given to third parties.

6. Carpenter v. United States, No. 16-402, 585 U.S.2018

Brief facts

There were a series of armed robberies using guns in which several robbers participated, subsequently 4 robbers were arrested. One of the arrested robber’s confessed regarding the crime and handed over his phone to the authorities. While reviewing the calls made by the arrested robber, the investigative agencies decided to collect details of 16 different phone numbers for all subscriber information’s, including call records, as well as cell site information for the target telephones at call origination and call termination for incoming and outgoing calls. One of the call details obtained was that of the petitioner, Timothy Carpenter who was later arrested on the basis of phone records. The Government was able to get access easily to these records, without any search warrant, as per the Stored Communication Act, (SCA) which enabled investigative agencies to get access to personal information by making statement that the same was required for an on-going criminal investigation. To obtain these documents by means of a search warrant, the investigative agencies were required to show a “probable cause” for such a search, which was difficult to get even in spite of the confession of one of the accused, because it requires more specific information. From the cell–site record the Government tracked that the petitioner Carpenter’s cell phone communicated with cell towers at the time and that Carpenter was within a two-mile radius of four robberies and on the basis of above information Government arrested and charged Carpenter for robbery and the jury later convicted him on several counts of aiding and abetting robbery and other offences.

7. The Supreme Court of United States by a majority of 5-4 decided that cell site location information details obtained by the investigative agencies without a warrant from the court violates the right to privacy of an individual which is protected under Section 4 of the American Constitution. Court held that simply because a third party is holding the information relating to a person he cannot be deprived of his right to privacy and an individual maintains a legitimate expectation of privacy in the record of his physical movements as captured through cell site location Information (CSLI).

8. Any activity on the phone generates CSLI, including incoming calls, texts, or e-mails and countless other data connections that a phone automatically makes when checking for news. CSLI data provides intimate window into the personal life illuminating all information regarding the user including his familial, political, professional, and religious and sexual association. Longer period of monitoring of an individual constitutes a search for which the search has to be authorised by a warrant from the court. CSLI was considered to be a distinct category of information as CSLI reveals personal information regarding the user all the time. Electronic eavesdropping for a long period was considered to be a violation of privacy of individual. Court also observed that every individual has a “reasonable expectation of Privacy”.

9. Prior to Carpenter’s case it was possible for the investigating authorities to obtain the cell site location information CSLI of a person without the warrant as the same has not been treated a search or as an invasion of privacy of an individual as protected by the 4th Amendment of the American Constitution. Later the courts seems to have taken into account the fact that cell phone has become an extension of human anatomy and that when the Government accessed CSLI from the wireless carriers, it invaded Carpenter’s reasonable expectation of privacy in the whole of his physical movements.

10. Carpenter’scase was a game changer, in the approach of the court regarding the concept of privacy. Court has recognised that the property protected from unauthorised search includes non-tangible information which was held by a third party, even if the owner has no control over them. While adopting new technological changes and the behavioural patterns of individuals in carrying cell phone to almost all places they go and had acknowledged this un-patterned situation to give new meaning to search.

11. If we consider the situation in India CSLI is prevalently taken by the investigating authorities without the permission of the court, behind the back of the user, to book offenders and in many cases investigation is solely depended on CSLI inputs without any qualification regarding the privacy of individuals. Privacy is that realm of an individual, where he is closed to reality and truth were he exposes himself to all vulnerable natural and personal instincts without the fear of being adjudged by the society. The territory of his privacy is that sensitive area of an individual, protection of the same from intrusion from outside is considered to be his natural right now progressed into a legal right.

12. Modern day cell phone has evolved from its primary function of a call connector to an “Aladdin lamp”, wherein a wish fulfilling “Genie” in the form of an “APP” does all function for you, except for some essential biological needs; nevertheless for some people even genetic needs are also taken care by the cell phone in a more satisfying manner. If cell phones have to be considered as “Black box” of parallel personal life of an individual, it is entitled for the same protection as is available for an individual against forceful recovery of information form himself. Protection against violation of privacy has to be extended not only to the person of a person but to his extension in electronic form as well. Now the situation that exists in our country is that a police man can easily take your mobile phone as per his subjective decision as to its importance in investigation without any accountably concerning the protection of the contents therein and regardless the graveness of the injury to which he is exposing the user of the mobile phone. It was reported that United Kingdom that police was widely using a Israel software called CELLIBRITE7 as an Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED). An UFED software can, in a matter of minutes, retrieve data from thousands of different mobile phone models. This data includes text messages, emails, contacts, photos, videos, and GPS data. WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram encrypted chat history databases, and Facebook messenger are all easily obtainable. There is also wide spread use of street level surveillance device by law enforcement agencies called STINGRAYS8 or IMSI catchers. They are cell-site simulators which duplicate as mobile towers by masquerading within a particular area as legitimate cell phone towers, tricking cell phones to connect to their device instead of original towers and copy information. STINGRAYS operate conducting a general search of all cell phones within the device’s radius, in violation of basic constitutional protections. Law enforcement use cell-site simulators to pinpoint the location of phones with greater accuracy than phone companies. Cell-site simulators can also log IMSI numbers (unique identifying numbers) of all of the mobile devices within a given area. Some cell-site simulators may have advanced features allowing law enforcement to intercept communications or even alter the content of communications9.

13. A cell phone in the hands of an investigative agency is prone to myriad misuse. They can copy your data in SIM/SD card; your Apps and browser can be opened to access personal communication establishing political, sexual and religious identities , emails, social media accounts picture and videos. Your personal identification information that links your phone with the user can be breached causing grave harm to the user. Cell phone contains not only information which are relevant to the investigation but other sensitive information about the user which needs to be protected from public view

14. Puttaswamy v. Union of India Supreme Court of India recognized that right to privacy is a fundamental right which emanates from Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. Constitutional and legal recognition of right to privacy creates a huge vacuum of law in protecting privacy as there is no positive legislation specifically protecting the same apart from the declaration by the court. Even Though Supreme Court decision has led the Central Government to enact THE PERSONAL DATA PROTECTION BILL 201910 which is yet to become law, the same does not completely address the protection of personal data viz., the infringement by investigation authority. In the absence of valid legal restriction, violations of privacy rights continue to be unchallenged and gross violation of law happens in the case of intimate personal data inside the mobile phone is easily intruded by the investigation authorities without any accountability.

15. If cell phone has to be treated as an extension of the personality of the user. Then the provision of law available (161(2) CRIMINAL PROCEDURE CODE) to a person to refuse

to answer any question which tends to implicate him for offence should be extended in case of cell phone and no person can be compelled to state the password of his mobile phone to the investigative authorities. At least the requirement of obtaining a warrant from the court to peruse cell phone information will definitely act as a regulator.

16. The new thought process inspired by technological advances to consider your cell phone as an extension of your anatomy seems justified by the pragmatic reality in vogue. CSLI is a main investigative tool for the law enforcing authorities in the matter of collection of evidence. Intrusion of personal data in cell phone is not confined to the accused in course of investigation, witnesses and all persons coming within the preview of investigation is a potential victim of misuse of cell phone specific legal provisos regarding the extent to which investigating authorities can peep into your personal data in your cell Phone.

17. Cell phone is a place where sensitive information about the user is safely kept .Present-day experience is that cell phone follows the user wherever he goes revealing all information of his travel and his private affairs in the form of CSLI and other applications inside the cell phone. The need to consider these information as sanctified by bringing them within the domain of “Right to privacy” and protecting them from unregulated intrusion seems to be a demand justified with reasonable cause and perfectly in tune with the reality.

18. Your digital belonging does have a legal status of “property”. There is no legal provision as in the case of search and seizure as per Section 91 to Section 105 of the Criminal Procedure Code at least to regulate search of personal data in case of cell phones. When your person or dwelling is protected from unregulated search, there is no justification in not extending the same protection to more intimate information having the status of a property.

19. If the concept of privacy envisaged in Carpenter’s case is adopted by the Indian Judiciary, then the same is going to affect the pattern of contemporary criminal investigation in the country and the investigative agencies will have to acknowledge the doctrine of E-PRIVACY. If right to privacy is s constitutional right then cell phone users has a legitimate expectation that their cell phone information are not meddled with by the law enforcement agencies unscrupulously. The issue is grave while we consider the fact that mobile phones provide a most comprehensive data about a person’s personal and public life and there is an alarming development in the use of mobile phones in India. It is estimated that there will be around 500 million mobile phone users in India by 202311. The ease at which the investigating authorities can unlock your private life coupled with their coercive powers espouses severely ethical, moral and legal questions. Even when we transcend this ignorant bliss regarding the safety of your personal information, we are given a choice less awareness, whether to crave for a potentially peaceful law and order system, where you are ready to sacrifice your privacy rights to the law enforcement agencies or to religiously stick to your fundamental right of privacy inviting the risk of diffusing the technical advantage of investigative authorities thereby indirectly helping the criminals.

Foot Notes:

1. No.16-402, 585 U.S. ____ (2018)Timothy Ivory Carpenter v. United States. The United States Supreme Court by 5–4 decision authored by Chief Justice Robert that the government violates the Fourth Amendment of American Constitution by accessing historical CSLI records containing the physical locations of cell phones without a search warrant.

2. Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) and Anr. v. Union of India & Ors. (2017 (4) KLT 1 (SC) = (2017) 10 SCC 1, is a landmark judgment of the Supreme Court of India in which it was held that the right to privacy is protected as a fundamental constitutional right under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

3. The Constitution, through the Fourth Amendment, protects people from unreasonable searches and seizures by the Government. The Fourth Amendment, however, is not a guarantee against all searches and seizures, but only those that are deemed unreasonable under the law.

4. The Stored Communications Act (SCA, codified at 18 U.S.C. Chapter 121 §§ 2701–2712) is a law that addresses voluntary and compelled disclosure of “stored wire and electronic communications and transactional records” held by third-party internet service providers (ISPs). It was enacted as Title II of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA).

5. United States v. Miller,425 U.S. 435 (1976), decided by United States Supreme Court which held that bank records are not subject to protection under the Fourth Amendment.

6. Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S.735 (1979), was a Supreme Court case, holding that the installation and use of a pen register was not a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and hence no warrant was required.

7.Cellebrite is an Israeli Digital Intelligence company that provides tools that allow organizations to better access analyze and manage digital data. The company is a subsidiary of Japan’s Sun Corporation.

8. The Sting Ray is an IMSI-catcher, a cellular phone surveillance device, manufactured by Harris Corporation. Initially developed for the military and intelligence community, the Sting Ray and similar Harris devices are in widespread use by local and state law enforcement agencies across Canada, the United States, and in the United Kingdom. Sting Ray has also become a generic name to describe these kinds of devices.

9. https://www.eff.org Electronic Frontier Foundation.

10. The Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 (PDP Bill 2019) was tabled in the Indian Parliament by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology on 11 December 2019 the Bill is being analyzed by a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) in consultation with experts and stakeholders. JPC has sought more time to study the Bill and consult stakeholders.

11. www.statista.com Statista is a German company specializing in market and consumer data.

A Tribute to Sri. J. Jose Vakil

By Justice V. K.Mohanan, Former Judge, High Court of Kerala

19/12/2020

19/12/2020

A Tribute to Sri. J. Jose Vakil

(By Justice V. K.Mohanan, Former Judge, High Court of Kerala)

“Those we love never truly leave us. There are things that death cannot touch.” --Jack Thorne

Adv. J. Jose, fondly known to us as Jose Vakil - my mentor! A perfect gentleman has been lost forever. Except a formal expression of condolences, in Advocate groups and social media, no tributary words were written for him.

Since 5th December, 2020, the day he left us, I’m being haunted by his fondly memories. Even if I go to bed on time as usual, I find it hard to fall asleep thinking of him.

I wake up in the middle of night and find it difficult to resume sleeping again. I must say that he has been a vital part of my life. Thus, I feel it inevitable and better for myself, to share my experiences with him.

Though I enrolled as an Advocate in 1983 and joined the office of Late Sri. M.K.Damodaran, Advocate, Ernakulam, I started to concentrate in my actual practice only in 1984 as I had to complete some social activities that I had been part of. Mr.Jose was one of the juniors in the office. I believe that I must also mention the advocates who were in the office along with me and Mr.Jose, under the efficient leadership of Sri.M.K.Damodaran, to make the tribute complete in its true sense.

Shri. M.K.Abdul Khader (Rtd. Judge, Vigilance & Anti-corruption, Tribunal) Father of Justice A.M.Shaffique (sitting High Court Judge), Retd.Chief Judicial MagistrateShri.John L. Akkara, and Adv. V.K. Raveendran, were attending the office as guest juniors and they are no more.

Besides them, the actual juniors were Shri. P.V.Mohanan, Shri.Johny K.Sebastian, Shri.N.N.Ravindran, Shri.C.T.Ravi Kumar (sitting High Court Judge), Smt.Saira Ravi Kumar, Shri.Salil Narayanan, Shri.Vincent, Shri.Alexander Thomas (sitting High Court Judge), Shri.Anil Kumar, Smt.Beena Anil Kumar, Shri.P.K.Vijaya Mohanan, Shri.P.Sanjay, Shri. O.V.Mani Prasad, Shri.Alan Pappaly, Shri.Sabu Edathil, Shri.Tharian Joseph, Shri. P.O.Joseph, Shri.V.Amaranath, Shri.M.Sasindran, Shri.P.C.Sasidharan, Shri.Mohan Raj, Sri.Gigi Poothecot, Sri.Manoharan, Late. Sri.T.S.Rajan, and Late Sri.M.Prabhanandan who was the son of the elder brother of Sri.M.K.Damodaran.Sri.K.V.Cherian and Sri. K. A.Rajuwere the clerks.

Adv.Jose had started his practice in a Mofussil Court at Ponkunnam along with his relative and senior advocate, Sri.P.D.Joseph. Thereafter, he shifted his practice to Ernakulam and joined the office of the veteran Civil Lawyer Adv.M.C.Sen.

Adv.Shri.Vadakoottu Narayana Menon, the then leading criminal lawyer at

Ernakulam was a frequent visitor of Adv.M.C.Sen and eventually he came into contact with Adv.Jose as he sensed the intellectual capability and depth of knowledge in law of Adv.Jose. Thereafter, Adv.Jose was invited by Shri.Vadakoottu Narayana Menon to join his office. Our Jose Vakil accepted the offer and joined the office and began assisting him in leading criminal cases. I must remind you that Adv.Shri.Vadakoottu Narayana Menon was a Special Public Prosecutor in the famous Muvattupuzha Antharjenam Murder Case. Thus, Adv. Jose gained rich experience in Criminal Law.

Though the main works in the office of Late Shri. M.K.Damodaran were related to High Court matters, Adv.Jose was keen to take up trial court matters! I would say that his presence in Damodaran Sir’s office was a great relief to the heavy work load during that time. Also, his presence substantially increased the cases at the office relating to Trial Courts. Famous Soman case, Manimallyath Case, Nedumkandam Murder case, Sandal Oil case at Thalassery and election cases with respect to Shri.O.Bharathan and Shri. T.M. Mohammad are few cases in which Shri. M. K. Damodaran had obtained efficient assistance from Adv. Jose.

Meanwhile, myself and Adv. Jose became very close and he treated me like his own brother, particularly when he realised about my social background and financial conditions.

Though Adv. Jose had vast experience in Trial Courts and Criminal Law, he was not having independent brief, while we were together at the office of Shri.M.K.Damodaran. But, Damodaran Sir never objected his juniors from taking independent briefs and conducting cases thereon, as long as it didn’t affect the office works. I have obtained the help of Adv. Jose as I could not conduct cases independently when I was a beginner. He has always extended help to me with pleasure!

When I think of my memories with him, I would like to share one of the criminal cases in which he gave me instructions and assistance. One such case was where the accused killed his own ten days old infant and wife and surrendered before the police station with blood stained chopper which was used to commit the murders. The prosecution had mainly relied upon the F. I. Statement given by the accused, admitting his guilt. Adv. Jose advised me throughout the trial and he was the person who instructed me to go through the important criminal law judgments of the year 1962. Although the trial court convicted him, the High Court acquitted him. The case was argued in the High Court by Adv.Late. Sri. M.Prabhanandan, junior to Adv. M.K.Damodaran. The appeal preferred by the State was also dismissed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court.

A valuable advice has been given to me by my dear Adv. Jose. In a criminal case, the defence lawyer must have shaped the defences in advance on the basis of available materials and the settled legal propositions applicable in the particular circumstances. The cross examination must aim to extract evidence purportedly to reinforce such defence and to shape the arguments.

It is pertinent to note that Adv. Jose was least interested in publicity. But, he was undoubtedly a very popular criminal lawyer among the legal fraternity. Clients always preferred him in criminal matters due to his ability and experience. Accused in serious and grave offenses, blue collar and white collar crimes particularly corruption cases,always preferred him to defend them. He had maintained his professional morale while giving legal opinions based on the merits of the case. He used to accept the briefs only if the clients were ready to accept his terms and conditions. But, he never ever misled the clients to obtain briefs. At the same time, he used to be selective while accepting briefs. In deserving cases, money/fees was not at all a matter for him and he was generous in extending his help and skill to poor clients.

He always ensured to pacify and comfort his clients whenever they were anxious and tense during trials. Even when he was not a religious person, he used to advise his clients who were theists to pray and stay calm. That was his way of consolation! He was not a keen believer of religious rites. It was because of his instruction and wish that his body was cremated on a public crematorium. He was never interested in conducting his funeral as per custom.

We do know that an advocate joins the office as a junior with an aim to gain practical experience and exposure. However, learning actually depends on active and voluntary involvement in the office works during client counseling, discussions and arguments. Generally, Senior Advocates never find enough time to teach the juniors. But, Adv. Jose has been an exception. He was kind enough to enlighten me and others with his knowledge.

Apart from my official relationship with Adv. Jose, we also shared deep family bond. We always used to ride on his old Yezdi Motor Bike to go and inspect the crime scenes. Adv.Jose and his wife, Smt.Sophy Teacher were very close with my family. They had attended my wedding too. Kunoor, a famous hill station was one of his favorite places. We used to go there with family members. He always stood as support during personal crises of mine. When my daughter Chandni Mohan joined M.B.B.S., Adv. Jose was very happy like us and he talked to her a lot before her classes started. He motivated her to do her best with his kind and inspirational words.

He had also obtained a Master’s Degree from Pune University and Smt. Sophy was his campus mate of the same University. She got appointed as a Lecturer in French Language at St.Teresa’s College, Ernakulam. She retired as a Professor and thereafter they settled at Kudayathur near Thodupuzha. Their daughter Ruby got married and now she’s settled in Canada along with her husband Abraham and their daughter Nicky.

His thoughts and perspectives are commendable and are different from the common mass. He used to complain sarcastically that he stayed busy in his profession when he was supposed to enjoy sufficient time with his family. But, he led a very happy and peaceful life. He always felt that and also has told me that he cannot imagine himself lying in bed due to sickness. He never wanted to be a burden to anyone. I must say, his wish actually came true. His dream of healthy life and peaceful death has now become materialized. But, it still remains a great shock to me.

I console myself in the belief that my Jose Vakil shall always remain alive in our hearts and his memories would never die. Dear Jose Vakil, in life we loved you dearly, in death, we love you still. In our hearts, you hold a place, no one else will ever fill.

Legal Aid in India – The Evolution

By P.B. Krishnan, Advocate, High Court

14/12/2020

14/12/2020

Legal Aid in India – The Evolution

(By P.B. Krishnan, Advocate, High Court of Kerala)

Legal aid has come to be established as an essential part of the administration of justice in India. Equal access to justice, as a concept, has been laid on strong constitutional foundations and has become ingrained in the law of the land. The right to receive legal aid has been elevated to the status of a human right, an inalienable and non-derogable right of the needy. There is an enforceable right to receive legal aid and an institutional mechanism conceived by statute to regulate it.

Recently, the Country celebrated the 25th National Legal Services Day to commemorate the National Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 which was enforced on November 9, 1995. How did this transformation of the justice delivery system occur? What were the impediments in establishing this regime and how were the hurdles crossed? The answer to these questions involves a study of evolution of the legal aid movement in India and an assessment of the role of each of the organs of the State in establishing and sustaining it.

The pre-independence era contains only fleeting references to the concept of legal aid. The British perhaps realized that legal aid would empower the subjects to question them and compel them to be accountable to the letter and spirit of the law. They were obviously not keen on their authority being effectively challenged every time they wielded the vast powers that they had conferred on themselves. An institutional machinery to provide equal access to justice was absent. The Bombay Legal Aid Society, formed in 1924, was a stray instance of an organization offering legal aid. The procedural laws were, at best, ambiguous on the subject. The result was that a large number of persons were cast and confined in prison. It mattered little if they were political prisoners or debtors or persons accused of crimes. If they were indigent, the law and the system did little to help them to establish their legal rights. In an adversarial litigation oriented system, the lack of resources in a party to obtain effective legal advice and representation was mostly fatal to his cause.

A reference to the procedural laws of that era throws light on the framework within which the courts and the administrators functioned. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1861 and the later Codes of 1872 and 1882, conferred a right to counsel on the accused in a criminal proceeding. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 provided that every accused had right to be defended by a pleader 1. The amendment to that provision, introduced

in 1923 2, extended that right to any person against whom proceedings were initiated in a Criminal Court. The Courts looked at the procedural prescription of the Code of Criminal Procedure as a right to be defended by a pleader. A plain reading of the provision did not seem to create any substantive right in an indigent accused. If the accused was indigent the Courts did not read the provision as one casting a duty on the State to provide legal representation at State expense. The violation of the legal right conferred by the Code was inferred only in cases where the State put obstacles in the path of an accused, preventing him from engaging a counsel of his choice 3. The violation of Section 340 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898, became a technical argument, raised at the appellate or revisional stages of a case to claim an acquittal, rather than a substantive provision conferring rights on the accused at or before the trial of his case.

An early sign of judicial activism in the matter of legal aid was visible in a case decided by the Bombay High Court in 1926.4 One of the issues raised in that case related to the right of an accused to have access to his legal adviser. The court held that a prisoner had a right not only to be represented by a counsel of his choice in Court but also at earlier stages when he wanted legal advice. The concurring judgement delivered in the case contains a remarkable statement of law that the very State which undertakes the prosecution of a prisoner must also provide him, if poor, with legal assistance. There is, however, little evidence of this ‘stepping out of the shackles of the procedural laws’ being put to use to further the cause of indigent accused in the trial courts. The observation remained a moral lament of the criminal justice system of that era.

The right to seek legal advice and representation was extended to preventive detention matters and quasi judicial proceedings 5, causes to which the mandate of Section 340 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1898, did not strictly apply. In civil litigation, the law enabled an indigent litigant to approach a Court, to establish his rights, without paying court fee.6 There was, however, no right to access counsel at State expense in the conduct of a civil case. The concession in the matter of court fee was quite inadequate to ensure that the cause was decided correctly. The Constitution of India guarantees to the citizens a right to equality 7, a right to life and personal liberty 8, and a right to approach the constitutional courts for enforcement of the fundamental rights.9 These fundamental rights conferred on the citizens did not bring about any immediate change in the interpretation placed by the courts on procedural laws like S. 340 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1898.10

The Law Commission in its 14th report submitted in 1958, thought of making justice less expensive to the litigant. The Law Commission recognized that legal aid is not a “minor problem of procedural law but a question of fundamental character ”. The concept of “equality in opportunity to seek justice” was noticed to conclude that legal aid is an obligation of the State. In 1972 an expert committee on legal aid was appointed to examine the various issues relating to legal advice, legal aid and formulation of suitable schemes to aid the weaker sections of society. The expert committee submitted a report titled ‘Processual justice to the people’ in 1973. The report recognized the link between Crime and Poverty and identified various special groups that were in urgent need of legal aid like agricultural labourers, industrial workers, women, children, Harijans, minorities etc.,…...

The report wanted legal aid to be available right from the stage of interrogation of the arrested person. The expert committee recognized and elaborated on the problem in great detail but did not suggest the institutional frame work or scheme to make effective legal aid a reality. In spite of the views of the expert committee aforesaid and the recommendations made in the 48th report of the Law Commission submitted in 1972, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 197311 only provided for a right to a pleader at the trial of a case by the Court of Sessions at State expense, if the accused did not have sufficient means. The provision did not imbibe the letter and spirit of the recommendation aforesaid. The rules made by the various High Courts under Section 304(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, also did not go far enough.

The amendment to the Constitution, introducing Article 39A 12, made providing legal aid a directive principle of State policy. The Judicature Committee appointed in 1976 went into the specific issue of ‘establishing and operating comprehensive and a dynamic legal service programme …. including formulation of scheme(s) for legal services’. The Judicature Committee wanted an institutional set up for the delivery of legal services not as a department of the Government but as an autonomous institution. The report submitted in 1977 was revolutionary but not much was done to implement it. The growing recognition of the need to make legal aid available to all those who needed it was slowly ingrained in the mind of the administrators and the judiciary. The studies, reports and constitutional amendment introducing Article 39A were all well intentioned. Without an institutional mechanism and a legally enforceable right to receive legal aid there was no real progress as far as the citizenry was concerned. Some high constitutional authority had to step in to make meaningful and practically beneficial progress in the matter. This was a period of time when the Supreme Court of India had started to look at creative interpretations of the constitutional safeguards by reading due process into the statutory provisions and compelling a fair and reasonable procedure to be followed while enforcing the law. Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India13 fundamentally altered the approach of the courts to the interpretation of Articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution and the manner in which the Indian

legal system treated issues relating to life, liberty and procedure.

This approach of the Court soon permeated the issue of legal aid as well. In MH. Hoskot v. State of Maharashtra14the Supreme Court declared that the right to legal representation at State expense is a fundamental right. The directive principle of State policy enshrined in Article 39A of the Constitution was used as an interpretative tool to reach this conclusion. The right to life, liberty and equality enshrined in the Constitution was decisively extended to make legal aid an enforceable fundamental right. In later decisions the Court proceeded to hold that legal aid is a matter of State duty and not Governmental charity15. The approach resembles that adopted in Powell v. Alabama16 where the United States Supreme Court held that the Court must provide counsel to defendants in Capital trials, i.e., trials where capital punishment is a possible sentence, if the defendants were too poor to afford their own counsel. This principle was later extended by the US Supreme Court to all federal trials in Johnson v. Zerbst17 and to all State courts in Gideon v. Wain Wright.18

A similar process, of expanding the scope of the declaration originally made was done by the Indian Supreme Court also through a series of path breaking judgements. Hussainara Khatoon & Ors. v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar19 dealt with the case of a large number of under trial prisoners languishing without trial in the jails of Bihar. While underscoring the need to ensure a speedy trial of the accused the court also held that legal aid is the “delivery system of social justice” and that failure to provide free legal services could vitiate the trial and violate Article 21 of the Constitution. In the case of Khathri & Ors. v. State of Bihar & Ors.20the Supreme Court held that the “State is constitutionally bound to provide such aid not only at the stage of trial but also when they (accused) are first produced before the Magistrate or remanded from time to time and that such right cannot be denied on the ground of financial constraints or administrative inability or that the accused did not ask for it.” The other remarkable statement of law found in the later directions issued in this case is the declaration that “the right to free legal services is an essential ingredient of reasonable, fair and just procedure for a person accused of an offence and it must be held implicit in the guarantee of Article 21 that the State is under a constitutional mandate to provide a lawyer to an accused person if the circumstances of the case, and the needs of justice so require.” In partial recognition of the reports and judicial pronouncements aforesaid the Committee for implementation of Legal Aid Schemes, 1980 was established.

The same positive approach to legal aid was shown by the Supreme Court while applying the provisions of civil law. Order XXXIII of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 enabled an indigent to seek relief in a Court without payment of court fee. The Supreme Court extended this benefit to auto accident claims holding that “the poor should not be priced out of the justice market by insistence on court fee….21”: The extension of the beneficial provisions of the Civil Procedure Code to Tribunals, which only have the trappings of a Court and are not courts stricto senso, gave relief to a large number of litigants. The decision was arrived at by enforcing the equality clause and directive principle to provide legal aid and reading the constitutional mandate into the procedural law. The concept of reading the statutory provisions in such a manner as to subserve the constitutional mandates became firmly established in the legal system.

The right of a detenue to consult a legal adviser of his choice for any purpose was held to be not limited to criminal proceedings but also for securing release from preventive detention or for prosecuting any civil or criminal proceedings22. The Court also had occasion to punish a lawyer found guilty of misconduct to engage in legal aid work for one year in lieu of the punishments prescribed by the Advocate’s Act, 196123. The question regarding the institutional mechanism for making legal aid available to the deserving and the advisability of leaving legal aid matters to the State and administrators was considered by the Supreme Court in the case of Centre for Legal Research and Anr. v. State of Kerala.24 The Court wanted public participation in the legal aid programme. The reasoning of the court was that since legal aid is the entitlement of the people, those in need of legal assistance should not be looked upon as mere beneficiaries of the legal aid programme. They should be regarded as participants. Sheela Barse v. State of Maharashtra 25reiterated the view of the Supreme Court that free legal assistance at State cost is a fundamental right of a person accused of an offence as it may involve jeopardy to his life or personal liberty. The Court, however, clarified that free legal assistance may not be provided in certain categories of cases, like economic offences, offences under laws prohibiting prostitution, child abuse, etc. The Court held that the trial of an accused who went unrepresented by counsel and was consequently convicted, is vitiated on account of a “fatal constitutional infirmity”. In A.K.Roy v. Union of India 26 the Supreme Court, however, felt inhibited by the express language of Article 22 of the Constitution in granting the right of legal representation before the advisory board in a preventive detention matter.

InSukdas v. Union Territory of Arunachal Pradesh 27 the Supreme Court was confronted with a case where the trial was conducted by a poor accused in person. The High Court proceeded on the footing that though the accused was entitled to free legal assistance he had not sought such legal assistance and therefore the trial was not vitiated. The Supreme Court reversed that decision stating that “It would….. make a mockery of legal aid if it were to be left to a poor ignorant and illiterate accused to ask for free legal services”. Over a period of time steady progress was made by the Supreme Court in imposing and enforcing an obligation on the State to provide legal aid on the basis that public interest is the strategic arm of legal aid.28 Moral outrage on the state of affairs led to an enforceable right to receive free legal aid.

The Legal Services Authorities Act (Act 39 of 1987) was enacted in 1987 to replace the Committee for the implementation of legal aid schemes (CILAS), 1980. The Act remained still born in as much as the institutional machinery contemplated by the Statute was not constituted. This was noticed by the Supreme Court while dealing with a Public Interest Litigation concerning convicts in jail. The Supreme Court directed29 effective Implementation of the Act and under pain of contempt the directions were implemented. The long gap of 8 years between the legislation and the extension of the provisions of the Act (except Chapter III) on 09.11.1995 to all States makes it abundantly clear that States are not very enthusiastic about making legal aid a reality. Administrative lethargy in the teeth of constitutional and statutory obligations is evidence of the lack of priority for legal aid matters in the mind of the administrators.

The framing of laws and schemes, without effective implementation is, hardly sufficient. The legal aid regime in India has firm constitutional and statutory foundations. But, the process of making legal aid available to all those who need it in a meaningful manner is only taking shape. Progress is slow 30. The transformation required by the Constitutional mandate and the decisions of the Supreme Court is still far away. May be, there is cause for the Court to step in again to speed up the process and to ensure that its vision is translated into reality. The Court has continued its pro-active role in the matter of interpretation of the provisions of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 so as to make the institutional machinery effective.31

An important interpretative or persuasive aid has become available on account of the march of International law in the matter of legal aid. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that every one has the right to life, liberty and security of person32, that no one shall be subject to arbitrary arrest, detention, or exile 33 and that every one charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty.34 The United Nations International Covenant on civil, and political rights (ICCPR) not only protects the inherent right to life 35 but also provides that an accused should have legal assistance provided for him “in any case where the interests of justice so require” 36. The Convention on International Access to Justice assures the nationals of contracting States and persons habitually resident in any contracting State to legal aid for proceedings in civil and commercial matters in each of the contracting States 37. The obligation of a nation State to international law has persuasive value for enforcing a right to fair trial and legal aid.

A case in point is Dietrich v. The Queen38 decided by the High Court of Australia, which relied on Article 14(3) of the U.N.International Covenant on Civil and Political Right, to which Australia is a signatory.

The decisions of the Supreme Court of India in the matter of legal aid have accelerated the process of securing equal access to justice to the citizens. The court recognized the link between law and poverty. The inequalities that exist between the haves and the have-nots in an adversarial system of litigation was sought to be bridged using the mechanism of legal aid39. In the course of giving content and meaning to the right to life and equality enshrined in the Constitution the Court held that access to justice is basic to Human Rights and the Rule of law. The Supreme Court could cast an obligation on all the organs of the state to fulfill a constitutional mandate to ensure the protection of the Constitutional and legal rights of the poor, the underprivileged and the neglected. In short, the court fashioned remedies for the indigent and deserving citizens by enforcing a legal aid mechanism as part of the law of the land. The Constitutional Courts have a growing role in ensuring equal access to justice and to transform the issue of legal aid to one of constitutional dimensions. This is a task that the Indian Supreme Court has achieved by innovative use of Public Interest litigation and the legal aid mechanism that is in place today is beholden to this organ of the State.

Foot Notes:

1. Section 340 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 reads: Every person accused before any Criminal Court may of right be defended by a pleader.

2. Section 340 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898 as amended in 1923 reads: Any person accused of an offence before a Criminal Court or against whom proceedings are instituted under this Code in any such Court, may of right be defended by a pleader.

3. Mannargan v. Emperor (AIR 1925 Mad.1153).

4. Re. Llewelyn Evans (AIR 1926 Bom.551).

5. P.K.Tare v. Emperor (AIR 1943 Nag.26).

6. Order XXXIII of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908.

7. Article 14 - Equality before law.

8. Article 21- Protection of life and personal liberty

9. Article 32- Right to Constitutional Remedies

10. Janardhan Reddy v. State of Hyderabad (1951 KLT OnLine 819 (SC) = AIR 1951 SC 217); Also see State of Punjab v. Ajaib Singh, (1953 KLT OnLine 924 (SC) = 1953 SCR 254).

11. Section 304 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 - Legal aid to accused at State expense in certain cases

12. Article 39A of the Constitution of India inserted by the Constitution (42nd Amendment) Act, 1976.

13. Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978 KLT OnLine 1001 (SC) = (1978) 1 SCC 248); Also see Francis Coralie Mullin v. Administrator of Union Territory of Delhi (1981 KLT OnLine 1010 (SC) = (1981) 1 SCC 608); and Bandhua Mukthi Morcha v. Union of India,

1984 KLT OnLine 1212 (SC) = (1984) 3 SCC 161) where the Supreme Court has held that the right to life guaranteed by Article 21 includes the right to live with human dignity, free from exploitation.

14. 1978 KLT OnLine 1052 (SC) = (1978) 3 SCC 544.

15. Also see in this context Sunil Batra (I) v. Delhi Administration (1978 KLT OnLine 1013 (SC) = (1978) 4 SCC 494).

16. 287 US 45 (1932).

17. 304 US 458 (1938).

18. 372 US 335 (1963).

19. 1979 KLT OnLine 1045 (SC) = (1980) 1 SCC 81, the later directions issued in this case are reported in (1980) 1 SCC 91, 93, 98, and 108.

20. 1981 KLT OnLine 1025 (SC) = (1981) 1 SCC 623, the later directions issued in this case are reported in (1981) 1 SCC 627 & 635.

21. State of Haryana v. Darshana Devi, (1979 KLT 269 (SC) = AIR 1979 SC 855)

22. Francis Coralie Mullin v. Administrator of Union Territory of Delhi, (1981 KLT OnLine 1010 (SC) = (1981) 1 SCC 608) (supra).

23. V.C. Rangadurai v. D. Gopalan & Ors. (1979 KLT OnLine 1081 (SC) = (1979) 1 SCC 308); where the Court preferred to impose corrective instead of punitive punishment.

24 1986 KLT OnLine 1451 (SC) = (1986) 2 SCC 706.

25 1983 KLT OnLine 1224 (SC) = (1983) 2 SCC 96, 101 Also see Sheela Barse (II) v. Union of India (1986 KLT OnLine 1433 (SC) = (1986) 3 SCC 632), Sheela Barse v. Union of India (1993) 4 SCC 204, Sheela Barse v. Union of India (1995) 5 SCC 654.

26 1982 KLT OnLine 1009 (SC) = (1982) 1 SCC 271 – “We must therefore hold, regretfully though, that the detenue has no right to appear through a legal practitioner in the proceedings before the advisory board”. This lacunae has possibly been rectified by Section 12(g) of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, which entitles any person in ‘custody’ to legal aid.

27. 1986 KLT OnLine 1452 (SC) = (1986) 2 SCC 401. Also see Kishore Chand v. State of Himachal Pradesh (1990 (2) KLT OnLine 1128 (SC) = (1991) 1 SCC 286); where the

Supreme Court frowned upon the appointment of young and inexperienced counsel to

conduct cases as part of the legal aid programme. On the appointment of Amicus Curaie see Ram Deo Chauhan v. State of Assam (2000 (3) KLT SN 19 (C.No. 21) SC =

(2000) 7 SCC 455) and Hussain v. State of Kerala (2000 (3) KLT 805 (SC) = (2000) 8 SCC 129.

28 Sheela Barse (II) & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors. (1986 KLT OnLine 1433 (SC) =

(1986) 3 SCC 632).

29. See for the steps taken by the Court for implementation of the Act. Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee v. Union of India (1998 (1) KLT OnLine 1155 (SC) = (1998) 5 SCC 762).

30. See, Law & Justice In An Independent Nation – V.R. Krishna Iyer, The Hindu 21.09.2006, where the learned Judge says “…those and other pathological features make the legal system unapproachable for the common Indian who seeks justice in the Courts and alternatively in the streets. There is little native flavour in the legal praxis except the costly curial chaos, and adversary logomachy”.

31. See, Government of A.P. v. T.Anjaneyalu (2005 (1) KLT OnLine 1142 (SC) = (2005) 9 SCC 312),

P.T. Thomas v. Thomas Job (2005 (3) KLT 1042 (SC) = (2005) 6 SCC 478.

32. Article 3.

33. Article 9.

34. Article 11.

35.Article 6.

36. Article 14(3) – A similar protection is afforded by Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

37. Article 1.

38. (1992) 77 CLR 292.

39 S.Muralidhar, Law, Poverty and Legal Aid, Access to Criminal Justice (Lexis Nexis Butterworths) Page 396 – “Where yawning economic and social disabilities segregate the disadvantaged sections into areas of criminality and illegality and further disable them from engaging with the process that enmesh the Criminal Justice System, Legal Aid could provide the buffer that, at least, in part, mitigate the consequences of such inequalities. It remains an essential instrument in the transformation of equal access of justice from a formal to an effective right.”